Illustrations for covers and beyond

As a Certified Medical Illustrator with a specialization in molecular subject matter, I create visuals for clients across the world. Here are some of my top tips for cover designs, as well as a behind the scenes look at actual projects for research groups.

Cover illustrations

My top advice for journal covers is to plan ahead and think strategically about the design – both for reuse and resubmission.

First, plan ahead and allow at least a month to create a cover: one week to contact an artist, meet with them, and get a project proposal (including budget and timeline), and three weeks for production. My typical cover design timeline is 2.5 to 3 weeks. This allows for two sketch stages, a draft, and a final (which you’ll see samples of below), with feedback at each step.

If you’re already in a time crunch, an expedited project may be an option. The fastest I’ve ever designed a cover is 4 days. However these short timelines are dependent on production availability and prompt feedback, and are subject to expedition fees.

When planning a cover, think about reuse. I encourage clients to plan something that they could use on a lab website, institution press releases, presentations, or social media. Sometimes I’ll create an illustration for a lab, and though I always feel really good about our chances to land the cover, for whatever reason, the editors don’t choose it. (One of my covers lost out to a lightly photoshopped photo of a hand holding a hot sauce bottle. I like to believe we didn’t lose on artistic merit for that one).

And finally, consider resubmission. Oftentimes if a cover design is general enough, or has a related variation (more on that below), it can be submitted as a cover suggestion for multiple manuscripts. If it isn’t chosen as the cover with the first publication, it may have a second or third chance with later, related publications.

Here’s a behind the scenes look at three projects: one, a journal cover where the researchers didn’t have a concept at first; two, a journal cover with a starting concept; and three, a research highlight image for use in lab presentations and online.

The open slate cover

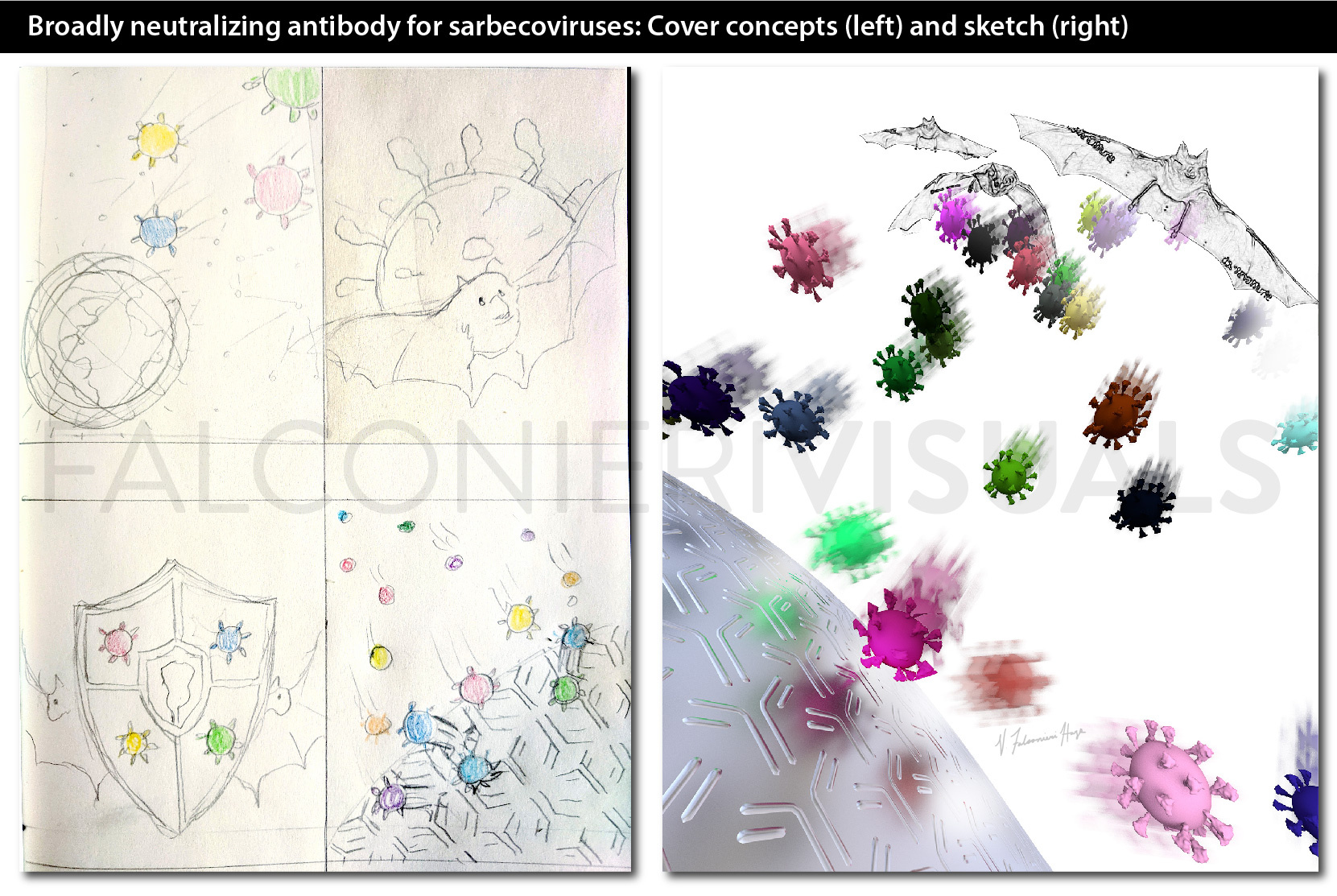

When David Martinez contacted me to create a cover design for his team’s publication about a broadly neutralizing antibody for sarbecoviruses, he didn’t have any ideas yet for what to show. I teleconferenced with Martinez and he gave me a high-level overview of their manuscript. From that discussion, I put together four pencil concept sketches for review. Though rough, these sketches capture the subjects and layout for a few different cover ideas.

I presented these to David, and we ultimately chose to proceed with the bottom right option, but flipped to so the viruses were coming from the top right, and including a version where the viruses were coming from bats, and a version without the bats.

I then developed a digital sketch, which includes 3D modeling and any additional 2D layers. I modeled the coronavirus virions in Cinema4D, using a PDB as the basis for a low resolution surface model of the spike protein.

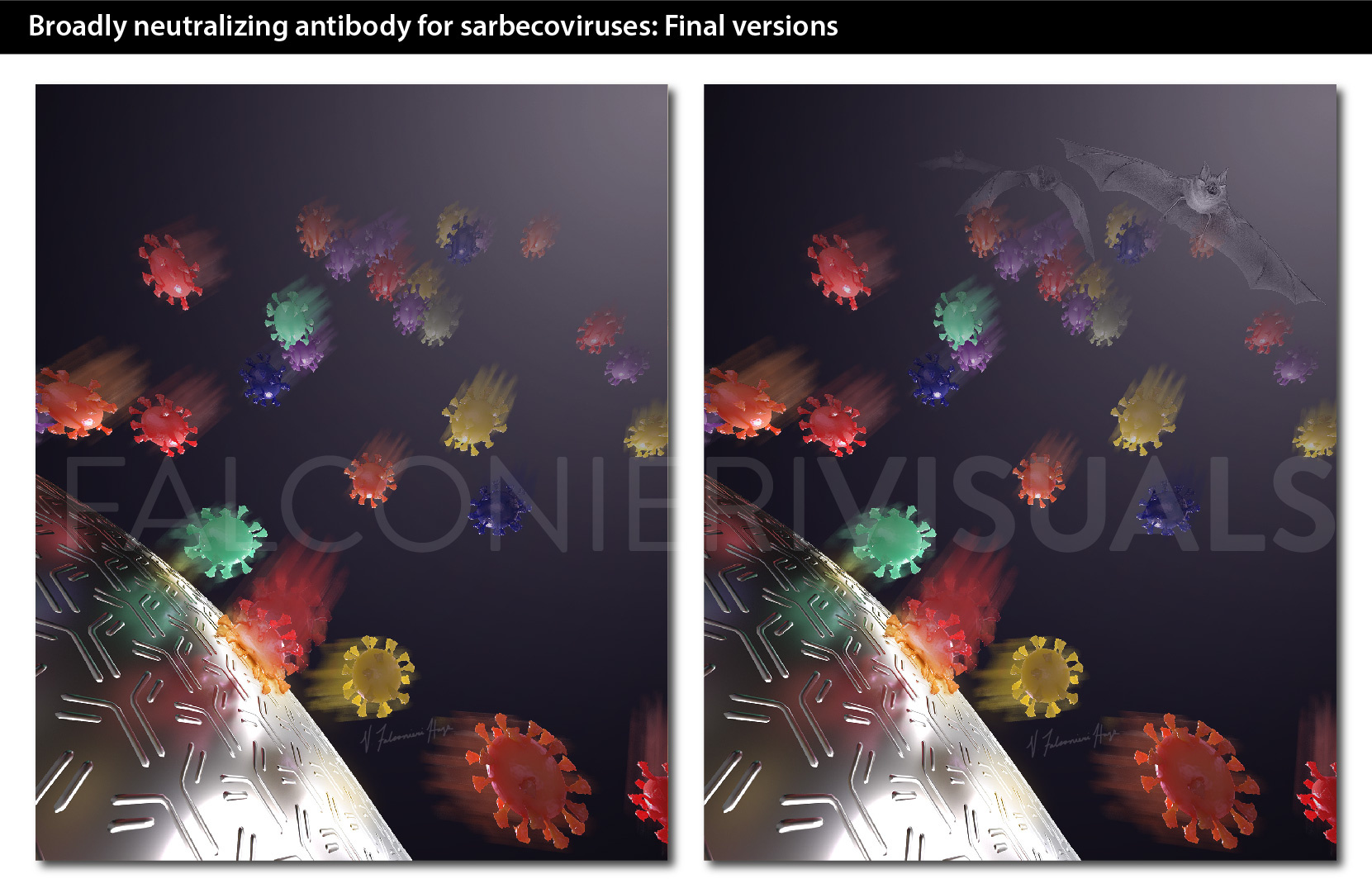

Once David had approved the digital sketch, I created the draft illustration. I always aim to make the “draft” illustration as close to final as possible, though some pieces may still be grainy or low resolution. Once the draft was approved, I prepared the final high resolution files.

This particular cover was selected to be the cover of Science Translational Medicine. The graphics editors had a few edits to the illustration, and I was able to update it quickly for their deadline.

Cover of Science Translational Medicine Volume 14, Issue 629, 26 Jan 2022. Illustration: Veronica Falconieri Hays/Falconieri Visuals

The cover with a plan

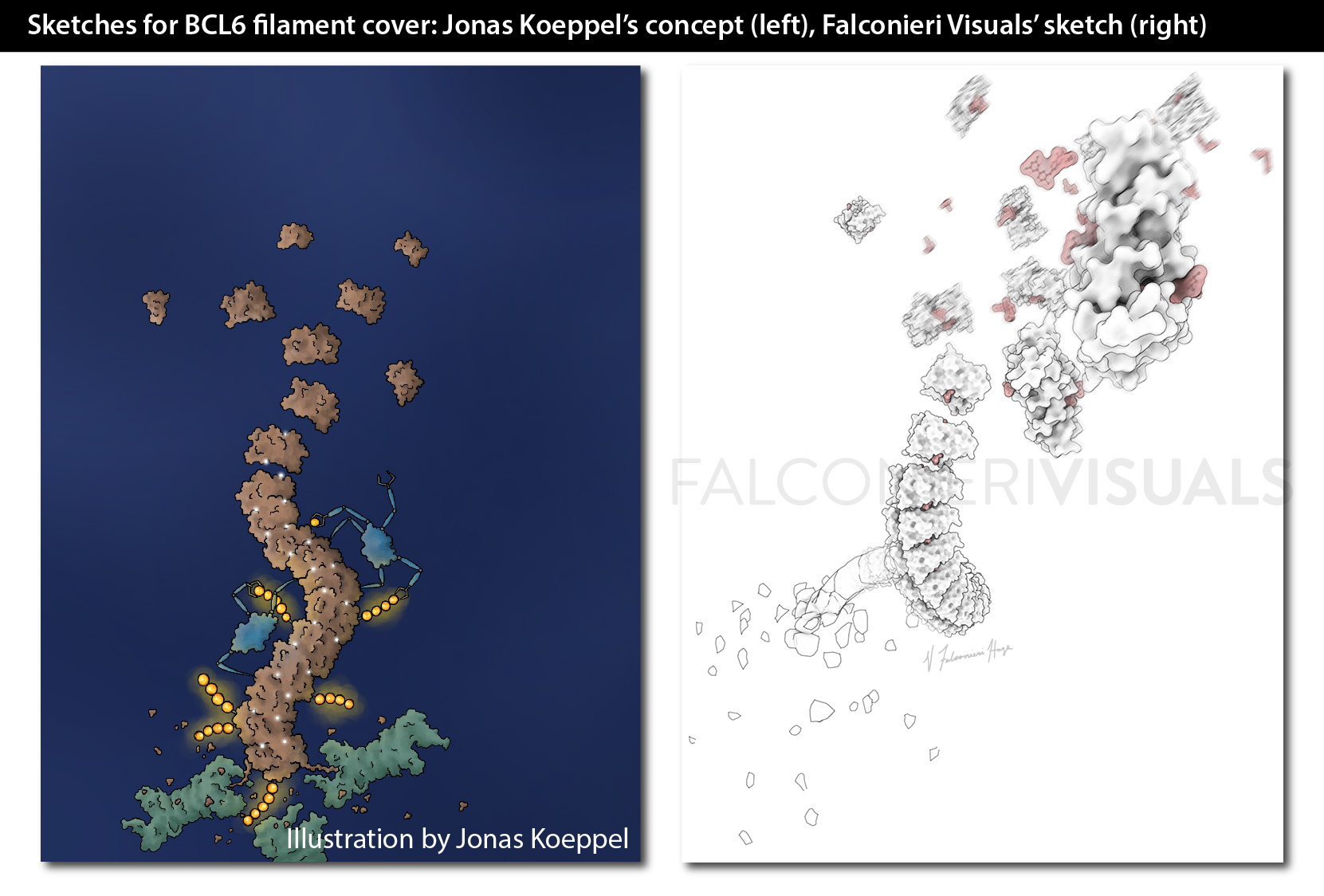

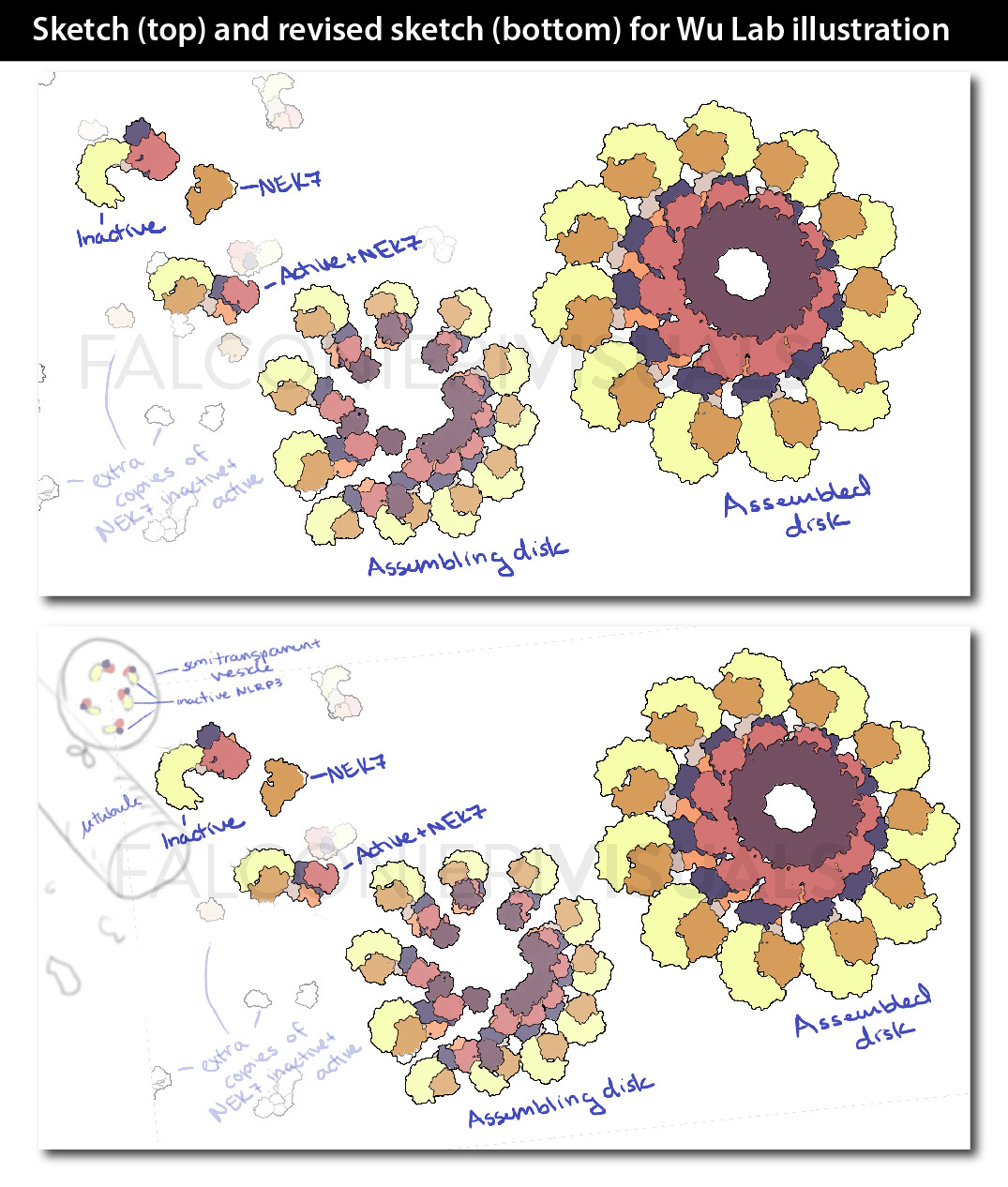

When I worked with Mikolaj Slabicki, Hojong Yoon, and Jonas Koeppel on their cover project, Jonas had already sketched an idea to capture their small molecule degrader for BCL6.

Quick side note – Jonas has a lot of artistic skill! To have a sketch this developed is highly unusual. Most scientists who I work with produce much rougher, but still just as useful sketches.

After an intro call, because their manuscript was going to be published in Nature, which has a track record of more minimalist, though visually striking covers, we decided to whittle down the concept to just the filament and an artistic representation of its degradation. If the paper would have been in Cell, Jonas’ whimsical design would have been a better fit. Mikolaj also requested two versions, one with the degradation effect and one without. This would allow them to submit the cover design again with a related but different paper, in case the current submission didn’t work out.

Since there was already a concept in place, I proceeded straight to the digital sketch. Hojong provided a PDB file of one helical turn of the BCL6 filament, and a PDB file of the dimer. I then recreated the filament in my 3D program, using Hojong’s filament PDB as reference to get the right diameter and helical turn, but with more editability to make it as long as I wanted and have it appear to be assembling at one end.

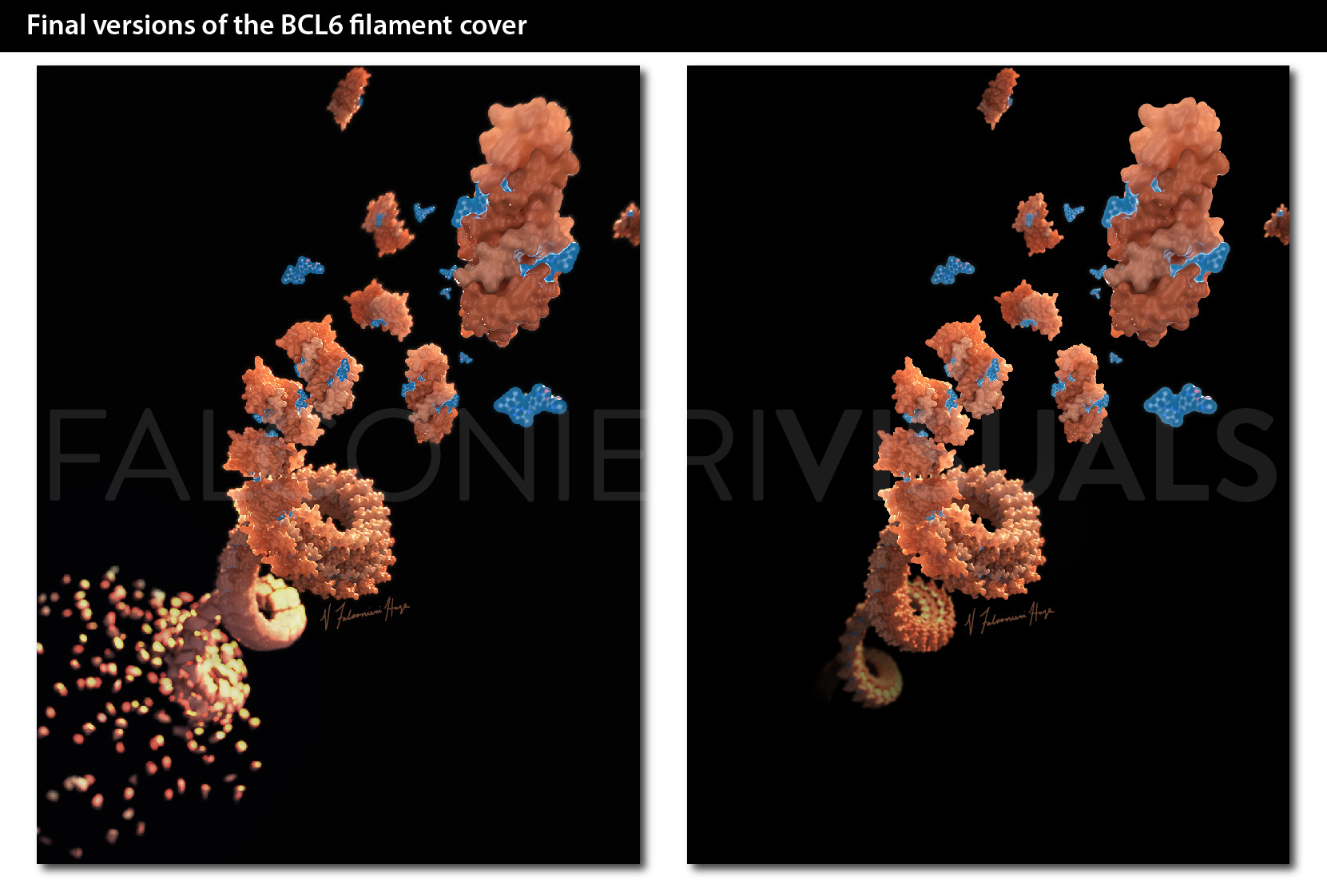

Mikolaj, Jonas, and Hojong provided great detailed feedback, including adding more turns of the filament’s helix into the composition. I then developed the draft illustration for both versions, and with a few tweaks it was finalized.

Though the version with degradation wasn’t accepted for the cover of Nature, the lab was able to use it as a nice slide background in the meantime. Then, almost two years later, the version without degradation was chosen for the cover of Cell Reports Methods to highlight BTBBCL6 dimers as building blocks for reversible drug-induced protein oligomerization.

Research highlight illustrations

Though covers are usually the first reason researchers think to commission an image, I’ve also created images for lab websites, social media, and presentations.

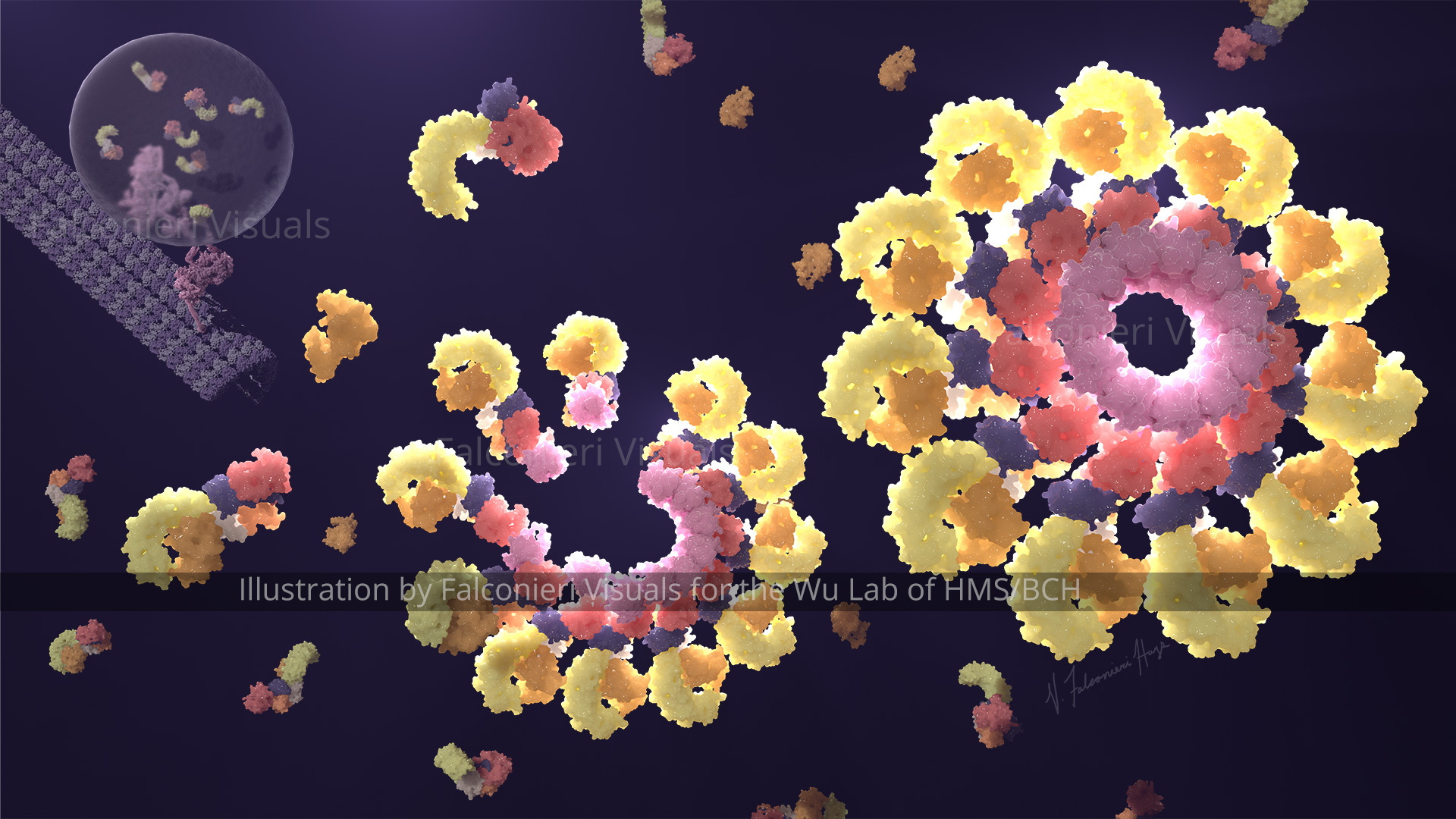

I created this image for Hao Wu’s lab in 2021 to summarize their current knowledge of inflammasome structures, including versions with and without a colored background so the image could be used flexibly within slides.

After a kickoff call with Hao and her team, I already had a pretty solid idea of the layout in my head, so I jumped right into the digital sketch. Hao’s team provided PDBs of all the pieces that I would need.

After reviewing the digital sketch, we added in one more step to the process, showing NLRP3 being transported along a microtubule. Before creating the microtubule and dynein model, I did a quick update sketch to confirm the new layout with Hao.

Once the updated sketch was approved, I developed the draft and final images with full color and lighting, and the Wu lab was able to start using them in presentations and lab social media right away.

I always enjoy working with researchers on these cover and highlight projects. I have a chance to learn about new science, and bring someone’s science to life in a way that exceeds their expectations. My goal is always to inspire interest, and share my love of the molecular and cellular with others.

Top image by Veronica Falconieri Hays / Falconieri Visuals

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.