What should I read?

A key challenge for experimental biologists and most scientists is how to keep up with a literature that is expanding at what seems to be an exponential rate. We need to know the literature that is directly relevant and obviously related to the projects we are working on. But we also need to be aware of important general developments and methodological advances outside our field(s) of focus, as such papers are important for our general scientific literacy, and may provide ideas and tools for future projects.

I approach this in two complementary ways. For project-specific papers, I do regular literature searches on PUBMED using broad keyword searches. My lab has a major focus on autophagy and I do a PUBMED search daily with “autophagy” as a key word, in order to identify relevant papers that I should look at. Papers will be selected if they are possibly relevant to projects we are working on and also if they may have general importance for the field. I then skim the abstracts and select the papers I want to download and print so I can look at them more carefully.

In order to identify papers outside my search terms that may be important to read, I scan the index pages of selected journals (generally on the days of publication of new issues). These include Nature, Science, Cell, Molecular Cell, Developmental Cell, Neuron, Nature Cell Biology, Nature Methods, J Cell Biology, eLife… One cannot scan the index pages of all journals, and thus one needs to select the journals that are most likely to publish major papers of general interest. I think that this is an important argument for a hierarchy of journals. In other words, PUBMED allows one to find all the papers of relevance to one’s specific projects, but the journal hierarchy provides a way to identify papers outside one’s narrow focus that are interesting and/or important.

Inevitably, the type of literature searching I have advocated yields more papers than one can read properly. Thus, one needs to prioritise papers into those that need careful scrutiny from start to finish (including those that are of immediate relevance to one’s project(s) and landmark papers of major importance), versus those that one can skim read. Skim reading can take various guises, depending on the paper – it can involve reading the entire text of the paper and only checking key figures, or even just reading key sections of the text with appropriate figures and relying on headings to guide one around other sections. I believe that it is important to cultivate the ability to skim a paper in 10 minutes or less – this then allows one to decide if the paper should be read in more detail, if it is suitably robust for one’s needs, and if it is novel/interesting/relevant. The ability to skim quickly and acquire a brief and crude overview of a paper is essential if one wants to be able to combine deep scholarship of the areas close to one’s project(s) with the necessary broader view of science.

It is good to be able to discuss important and relevant papers with colleagues. Thus, I strongly believe in journal clubs. My lab has one journal club each week and everyone is expected to attend. We spend around 40 minutes discussing one paper that was deemed to be important by the presenter – this task rotates around all members of the group. Papers for journal club are sent to all in the group before the meeting to allow individuals the opportunity to look at the study before it is presented. The presenter first gives a brief overview of the background and then presents all of the key data from the paper and its conclusions with Powerpoint slides in about 30 minutes. Then the presenter considers the strengths and weaknesses of the study, before the discussion is opened to the other attendees. I believe that this type of journal club is far more valuable than one that highlights the key findings of many papers – this can be easily accomplished in PUBMED searches and important papers can be sent around the lab using group/individual emails. A key benefit of the "40 minute – 1 paper" journal club is the possibility for in-depth discussion and consideration of relevance and impact for ongoing work, as well as training in paper reviewing and oral presentation for students and postdocs.

In conclusion, one’s reading strategies need to be able to address the balance of knowing as much as possible about one’s project and the acquisition of a broader scientific knowledge. The latter objective can also be aided by textbooks, podcasts, email newsfeeds, journal front matter or "News & Views" equivalents (e.g. in Nature and Science), and seminars.

Outside reading for “work”, we all read fiction and/or nonfiction. I enjoy reading biographies, including those of important scientists – among many excellent books in this genre, I recommend In Search of Memory (autobiography of Eric Kandel, who discovered long-term potentiation, the molecular correlate of memory) and American Prometheus (biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer, who headed up the laboratory that developed the first atomic bomb). I also think we should have some interest and knowledge of the history of science – I was fortunate to have an inspired High School English teacher who set The Ascent of Man (Jacob Bronowski) as our setwork book that we had to study from cover to cover. This wonderful book that covers many aspects of the history of science is a summary of a television series that Bronowski made for the BBC and many (if not all) of the episodes are currently available on YouTube. I strongly recommend this masterpiece – both the book and the television series. It is inspiring.

David C. Rubinsztein1,2*

1 Department of Medical Genetics, Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, Wellcome Trust/MRC Building, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0XY, UK.

2 UK Dementia Research Institute, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Hills Road, Cambridge, UK.

*[email protected]

Acknowledgements: DCR is supported by the UK Dementia Research Institute (funded by the MRC, Alzheimer’s Research UK and the Alzheimer’s Society).

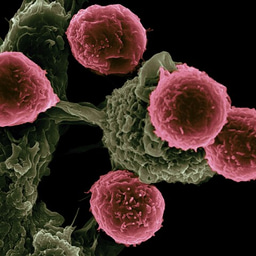

Top image of post: Black Jack / Shutterstock.com

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.