The life and work of a translational scientist

When I was asked to write a post for the FEBS Network about how I became a translational scientist, my first reaction was, sure, I'm having some travels ahead and writing in a plane or train is a nice activity. So here I am, sitting at the airport – on the way back from Philadelphia, where my friend and colleague from Nice, France and 12,000 other people attended the “Kidney Week”, the largest nephrology meeting in the world – and I want to share with you my career path and my passion for the work as a (translational) scientist.

I thought of studying medicine, but decided for biology in the end and I won't lie, botany and zoology were not really my cup of tea. I suffered through the first four semesters until we had a course in molecular biotechnology. I loved this! The potential of transforming medical care, the way how production of pharmaceuticals can be optimized, the way how we understand diseases and find new ways to treat them... Just take insulin as an example, what a groundbreaking advancement has been achieved through research! The advances have been tremendous since then: we now do routine genetic testing, and even have approved gene therapy. This semester I'm a guest lecturer at the university of applied sciences (Bingen Technical University of Applied Sciences | TH Bingen (th-bingen.de) teaching molecular biotechnology to students and while preparing my lectures I always learn about many fascinating, groundbreaking advancements. The technology has remarkable potential and I enjoy the application of novel methods to answer our research questions and in the end to gain insights into disease pathophysiology and identify therapeutical targets.

But how did I end up here? From Bratislava, Slovakia, not liking my first biology semester, to working in translational research at the Heidelberg University, Germany, one of the best medical universities in the world?

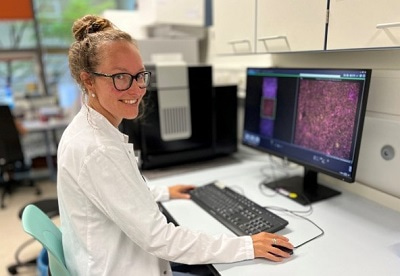

In the lab doing imaging analysis

Work hard at those opportunities

Since my bachelor studies, thanks to the support of my molecular biology lecturer, I had the chance to work in the laboratory and I enjoyed doing research a lot. Another milestone was an Erasmus exchange at the Uppsala University in Sweden; this was the time when I realized that, not only I wanted to work in research, but also ideally to work in an international team and to integrate some travelling into my future career. So, when I finished my master studies of biotechnology and was thinking about the next move, there it came: a PhD position in the European Training and Research Program in Peritoneal Dialysis – a PhD program within the Marie Curie Sklodowska Initial Training Networks (MSCA-ITN).

Where it all started, with my collegues from the EuTRiPD group.

Maybe you are now asking yourself: what does that mean? To be honest, I was not even sure what peritoneal dialysis was, when I applied. As most people, I was aware of hemodialysis, a kidney replacement therapy for patients whose kidneys do not work, and they can't be immediately transplanted. But peritoneal dialysis? Still, I applied and got the job! I moved to Heidelberg, Germany (which I had known only as the headquarters of EMBL, European Molecular Biology Laboratories) and started my doctoral thesis at the Heidelberg University Hospital as one of the 12 international students in the program. I defended my PhD with summa cum laude and got an award from the German Society for Nephrology. The defense was a great party with my mentors, parents and friends, who have always provided great support and inspiration.

Right photo: Award from the German Society for Nephrology for the best PhD thesis. On the right, Prof. Claus Peter Schmitt, my amazing mentor without whom it would not have been possible! Thank you!

Bedside to bench and back

I strongly believe that we can only achieve success and scientific progress with collaboration. I have been working closely with medical doctors, other biologist, biochemists, even with physicists. You get to know other points of view and I learn new things every day. Intersectoral collaboration teaches you to stay open-minded and to exchange and explain your own ideas better.

Working as scientist in the clinics reminds you why and for whom you are doing this. It's for the patients, and although the impact is not as immediate as when you work as a medical doctor, it is equally important. I manage a biobank of tissues from children whose kidney do not work and they require (peritoneal) dialysis (International Pediatric Peritoneal Biobank). We study the molecular machinery underlying the vessel changes, which unfortunately in many cases lead to cardiovascular complications in early adulthood. During my PhD we identified a specific signaling pathway, which was associated with such vascular changes in children on PD – a pathway becoming more and more studied in other diseases and representing a druggable target to improve patients’ outcomes. And indeed, we are now working with a biotech company who develop inhibitors of this pathway and we are testing them in pre-clinical setting. From the bedside to the bench and back: the translational approach that I like, and which will hopefully improve patients’ lives one day, also thanks to my contribution. This gives me a feeling that my work makes sense. In the following MSCA-ITN – improvepd.eu – in which I was a co-supervisor, we targeted the cardiovascular complications in PD patients on a systemic level. It has been another great experience, further strengthening the international network, as well as a new personal experience in the organization of an international workshop, and of course more science. At the moment I'm a fellow in the Elite Program supported by the state of Baden-Wurttemberg; my project aims at network-based understanding of vascular disease pathophysiology at the single cell level and with spatial resolution.

Attending the academy of the ImprovePD in Madrid, Spain.

Home and away

Attending conferences and the exchange with fellow colleagues is definitely an added value for my career. Of course, flying around half the world just to give one talk at a conference should be considered in view of climate change and, as with the most things in life, it's about the dose. Don't overdo it. But let's be honest, for those of us who enjoy to travel, it's great opportunity to see new places, meet new people, work and enjoy different cultures in one run. In Europe, I usually travel by train unless the distance is very far, but I also took the plane to attend conferences in faraway places like Singapore and Taiwan. It's work, but it feels a little bit like a holiday and when you meet international colleagues, from whom many became my close friends, it makes you forget the extra hours in the lab very fast.

And what does it look like back home? I would say no day is like the other, which is one of the things I mentioned earlier that I like very much. Some days are filled with experiments, others with meetings and discussions. Once you feel your results are worth telling the world, you need to sit down and write it together. Besides lectures in biotechnology, I give physiology courses for medical students, so on some days I'm just busy teaching and explaining how to hold a pipette properly. I spend time with organizational tasks, for the biobank and with my younger colleagues. Supervising students and inspiring (hopefully) the next generation are another part of the job I enjoy very much. It means working with bright, motivated minds, from whom I can also learn.

Teaching time. Waiting for my students in the physiology practice

Scientific career is a diverse job and of course it has its downsides, when an experiment doesn't work, the grant was not approved, or the paper is rejected. But if you have a supporting work environment, a good team and believe in your project, I know nothing better than science!

Our team of pediatric nephrology and dialysis research

Top image by the International Pediatric Peritoneal Biobank. Other images by the author.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.