Choosing where to pursue your research after your PhD is one of the most important and complicated decisions in the path of becoming an independent scientist. In biology-related fields, the postdoc research is quite long (4–6 years on average, unlike other fields with 1–3-year postdocs) which makes the location of your postdoc a big part of the decision. Moreover, the academic career track is very competitive and becoming more so as the years go by. For that reason, you want to do great research with significant impact, but also develop additional skills required for the PI position, like teaching experience and outreach, fellowships and grants writing, people management skills, networking, etc., which can also be beneficial for other career options later on. Taken together, this process is not easy!

Across two posts on the FEBS Network, I will discuss a few of the factors of the decision, and share my recent experience from this process.

To do or not to do?

In my personal belief, one shouldn’t look at postdoc research as an inevitable step after finishing a PhD. I truly think that after completing nearly 10 years of training you should stop, think carefully on what you want to do next and keep in mind the disadvantages; this track is long, not rewarding financially (sometimes even costs money) and there is no job waiting for you at the end. I will not go, in this piece, into the factors and reasons of the decision to do a postdoc or not. I will also not relate to the option of doing a postdoc in industry, but all of these are things that you have to keep in mind.

My tip: If you think you want to go for it, I suggest you go through the process of finding a postdoc lab and then, after you have your best option, go back to ask yourself “to do or not to do?” now that you have a concrete offer – to review your final decision.

When and where?

The general recommendation is to start your search 6–12 months prior to your desired starting date. Generally speaking, there is no ‘application season’ and people apply and interview all year round. Still, there are times like the winter holidays (mid-December to early January) and summer (mainly August) that are more likely for people to travel, and usually, the email response, as well as the availability of PIs, will be low. You don’t want to come and visit a lab when half of the people are on vacation. There is a slight advantage of starting the postdoc position with the academic year (September–October), because most people are back from vacation and there are courses starting if you want to join etc., but that definitely shouldn’t dictate your process. Another factor that you might want to consider is application dates and eligibility for fellowships. For most fellowships, you have to submit (or defend) your PhD thesis prior to the postdoc starting date, with some even asking for a final PhD approval. Keep this in mind when planning your timeline. The destination, of course, can be world-wide. If you have a bias to a certain place for different reasons, such as family or friends in the area, language, or opportunities for your partner (if there is one joining you), this is the location you should start from. If not, and you are open to moving everywhere, start with the subject (see next section).

My experience: I started the active search in March, roughly six months before my postdoc starting date (September). With this time frame, for a few labs it was already too late and they already had a few candidates for the following academic year, which meant that I should have applied in January. On the other hand, others didn’t have yet a clear picture of grants for the next year, so I guess you can never find the time that is good for everybody. Geographically, I narrowed the search to begin with to three cities that were more promising in terms of work opportunities for my spouse.

Ready, set, go…

There are many different ways to start the search, so no right answer to this question. Here is my suggestion:

1. Start with making a list of all the labs/PIs that you think are relevant. The broader and more detailed this list is, the more helpful it is in the process.

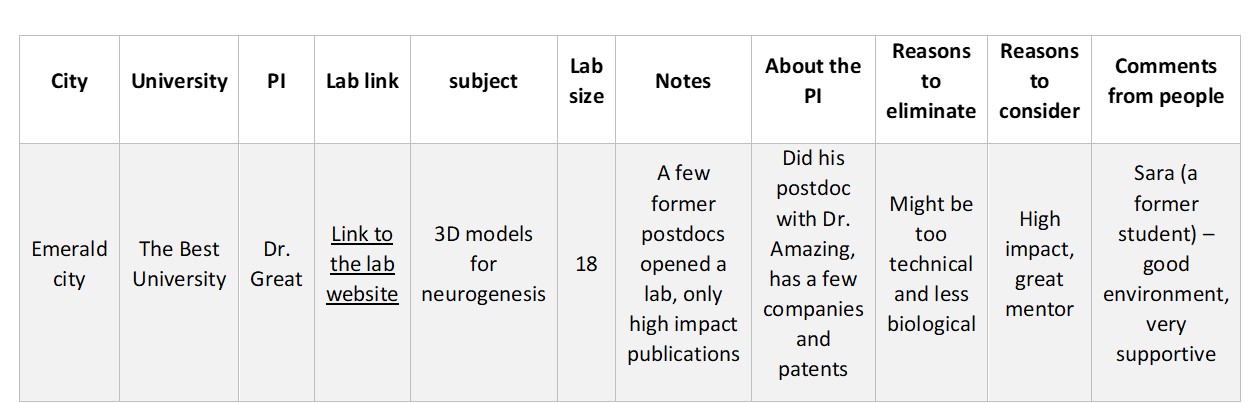

My tip: I made a table. The categories in my table:

Basic information – Location, number of people in the lab, and any relevant notes you can add.

About the PI – Relevant information you have from people who know the PI personally or just from online searching (e.g. when the lab was established, main collaborations…)

Reasons to eliminate – Red flags for you. This can be a cultural/personal thing that might bother you, or a professional aspect that doesn’t meet completely your desires (e.g. too small/big, the publications concern you, the subject is too narrow…)

Reasons to consider – Main advantage that caught your eye. It is very personal (e.g. an opportunity you see for collaborations, budget, PI personality…).

Comments from people – Find someone to ask directly about the lab. Can be a former student/postdoc, a person from next door lab, etc.

Here is an example:

2. How to add labs to the table?

- Labs where you know their research from papers, conferences, etc. You should keep it in the back of your mind during your PhD. You can easily create a list of labs that were appealing to you during your scientific journey and start by checking if one of them is actually right for you.

- Your PI – You can ask your current PI, and also other PIs you know (for example from your PhD committee) for their advice. You’d be surprised how many names can come up from a short conversation about your future directions. This will be an opportunity also to get some information about these options for your table, and to ask for assistance with an introduction [see ‘reaching out’ section in Part II].

- By subject – Google search your subjects of interest, with names of institutions relevant for you.

- By institute – Go to the institute website and search for relevant departments. Some have informative websites with a short description of the labs; some just have a list of names and you have to search one by one.

My experience: I did all of the above. Eventually, the lab I chose was that of a PI who had given an amazing talk during the first year of my PhD! My PhD PI also knows him and made the connection between us.

3. Now that you have all the data, you can start to focus and rule out based on your personal preferences.

My Tip: Find someone who knows the lab and ask about things that are important to you. I reached out to a lot of alumni or people from neighboring labs who gave me valuable information that I would never have known otherwise. I included all in the table and started to apply to the most relevant labs.

So now you’ve done the groundwork looking into the options and have your data. Next, in Part II: 'deciding and reaching out'.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.

This is how scientists choses, thank you.