Is knowledge really the primary product of academic research?

I am more than ever convinced that the most important output of research – relative to the level of societal investment – is the production of scientists.

From the outside, academic research looks like a fantastically wasteful activity. Literally millions of dollars of taxpayer money are invested in wringing secrets out of the natural world and developing new techniques, but a lot of the data generated using that money never gets published.

Some of it will not be publication-grade, some of it (“orphan observations”) is good but doesn’t find its way into a research publication, some of it ends up being replaced as a paper is revised, and some of it ends up sitting on the shelf, unpublished, for too long and becomes outdated.

Even high-quality data doesn’t guarantee a long half-life after publication. Individual papers, even highly influential ones, make a minimal impact by themselves, and the vast majority of scientific papers are not highly influential or even true breakthroughs, no matter what the hype merchants claim. It’s rare for a paper to be read or cited much after 5-10 years, and less in areas of high activity.

Faced with these kinds of outcomes, it’s perhaps natural that the public (and their political leaders) should be sceptical about whether this constitutes good value for societal investment, and perhaps explains why researchers will tie themselves in knots trying to explain the disease or health relevance of their research.

Because there’s a reason why “impact” sections of grants are so difficult to write and feel like a charade – deep down, we know that fundamental research is about generating knowledge, and that’s what we care about. That’s the impact. But there’s always an unease about saying that quite so nakedly. Forecasting impact is easy for applied research (possibly explaining its popularity with politicians) because it addresses an unmet societal need; fundamental research only addresses our need to learn more. It provides the raw material for innovation.

Every researcher is additionally affected by cognitive bias, because we all think that what we’re working on is one of the most interesting things out there, even though our nearest colleagues will probably disagree (because they naturally think that what they’re working on instead is one of the most interesting things out there).

So we tire ourselves out producing papers, but are continually rebuffed at the peer review stage – no matter how good it is, no matter how interesting we think it is, there will always be somebody (and often, many people) who simply don’t see it the same way.

This intense focus on our tiny little patch of research turf to the exclusion of much else (how many scientists are knowledgeable about specialisations outside their own?) warps and distorts our sense of perspective, as happens if we stare at something too closely for too long – we see the beauty of a single leaf, the intricate architecture of an ant, the sequestered secrets of the nucleus….yet that obsessive (and sometimes embittered) focus on the object of our research makes it easy to miss the people bringing it to light.

And perhaps that’s how it feels once you fully leave the bench behind, when you no longer do research with your own hands – like one of those scenes in a movie when someone sits still, fascinated at an object in front of them, while around them everything whirls and blurs in fast-forward. How fast ten years can pass on a research topic! How many people can pass through the doors of a lab, make their contributions to the object of fascination, and then leave almost unremembered.

This probably explains some of the extractive and exploitative practices in research. If the research is perceived as the most important thing, and the people doing it almost bystanders, then it becomes easier to appreciate why papers can get delayed for years even after students/postdocs – with a dragging handicap on their CVs – have moved on, why young scientists can be treated as disposable resources in pursuit of a longer-term aim, and why their struggles and problems can be received with unempathetic disinterest.

But there’s another way of looking at this system, and one which makes almost every cent expended look like a good investment – the human side.

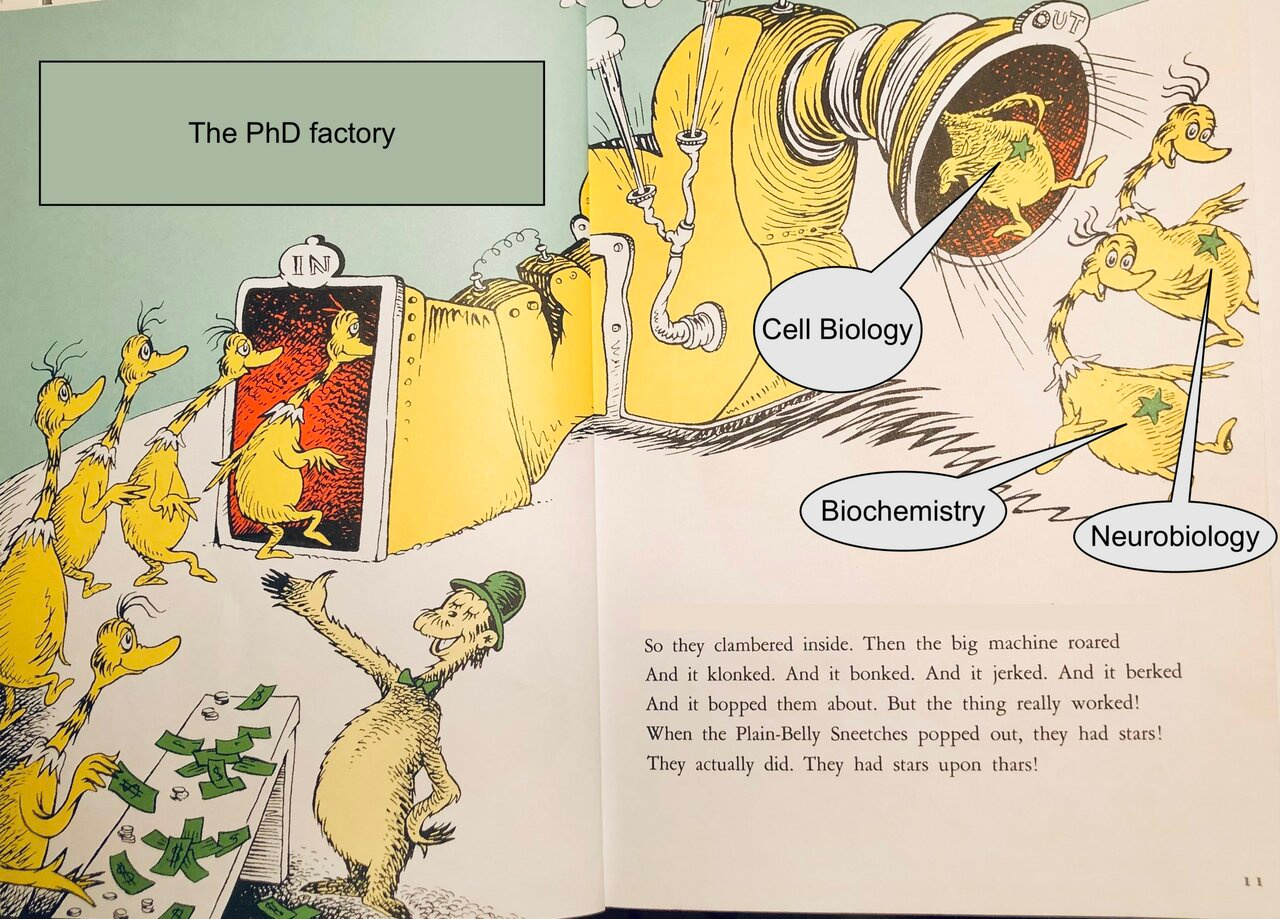

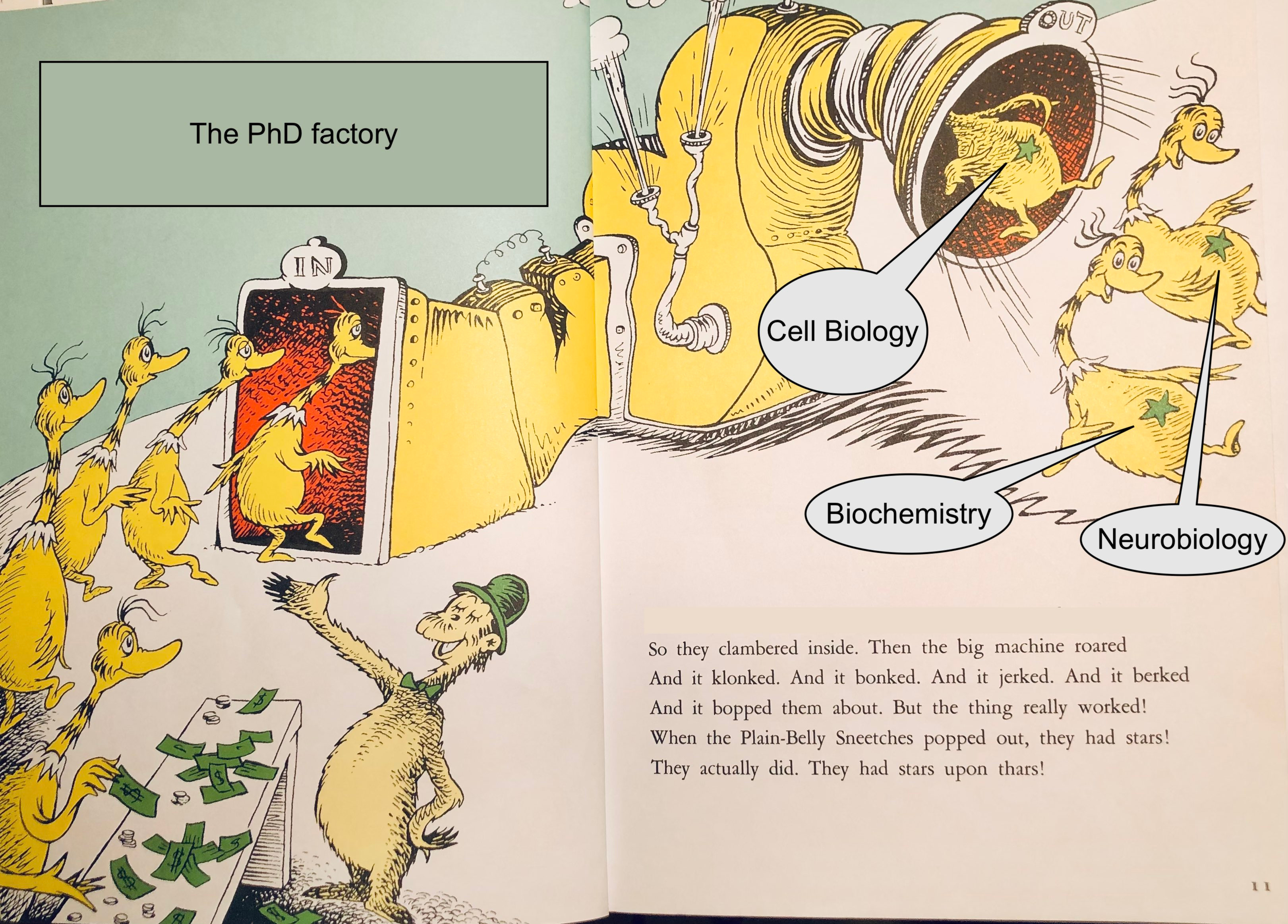

Because academic research doesn’t just produce science, it also produces scientists. And it is the scientists that are produced which represents the most tangible return on the level of societal investment. That is, undeniably, impact – the money is invested, and scientists are produced. Society ensures the production of more scientists.

Seen from this perspective, it is actually the papers – not the people – that are the (fascinating) by-product of this activity, and the quality of the papers produced partly reports on the quality of the training.

As a corollary, it is therefore important that those people, those scientists, can go out into the wider world with a positive sense of mission. They are the products of a significant societal investment, now equipped with the analytical tools to tackle real-world problems in a variety of spheres.

Scientists are needed more than ever in the industrial sector, in politics, in policy, in almost every facet of this increasingly data-driven world we live in. But the exceptionally research-orientated view of scientific output insists that these people are less important, and will never be more important, and should not be treated as more important than the projects they work on during their training.

This is a delusion, and a delusion which continues to cast a shadow over the lives of many smart, motivated, and driven young people, many of whom may well end up leaving academia not with a sense of excitement, but a sense of disillusionment.

Nothing could be farther from the reality – they are going where they are more needed, where they will be more welcomed, and where they will have a more tangible impact.

As scientists we dream of having a real-world impact but for academics, their most tangible impact is staring at us in lectures, in practical classes, and in lab meetings. The papers are not the product – the people are.

Originally published on Total Internal Reflection – here.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.