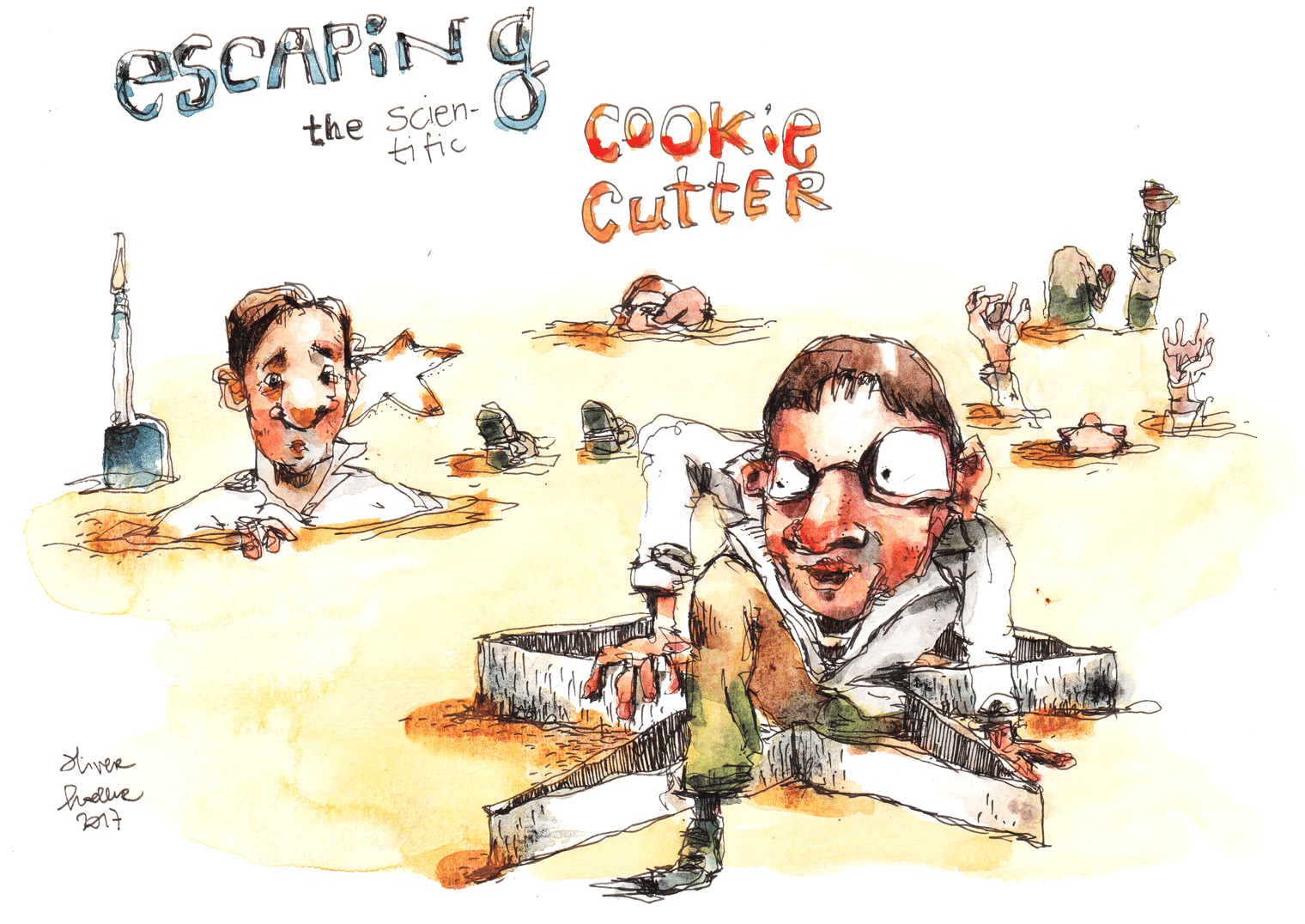

Students and postdocs cannot simply be clones of their mentor.

To a greater extent than many other professions, science relies strongly on personal relationships during the training and maturation period of its young members. Training is one-on-one; while there are plenty of workshops to facilitate acquisition of both hard and soft skills, there’s still no MBA equivalent where you attend a class with a group of aspiring peers. No certificate – not even a PhD – gives you an automatic licence to start your own group, and who you’ve worked with can often be more important than where you worked. In other words, it’s still a guild system in many respects, where you apprentice yourself to a master in order to learn at first hand the secrets of their art.

However, in order to become an independent master in your own right, it’s important that you develop your own style, your own way of doing things. The problem is that these days it’s unlikely that you – and possibly your boss too – will have sufficient time in career terms for you to luxuriate in organic growth.

Consequently, it’s quite likely that your boss will steer you through your project quite closely (either forcefully or gently). Their motives for this might be altruistic (they want you to do well and know the risks of running out of time) or selfish (there’s indirect or direct benefit for them if your paper/fellowship is accepted). Probably both.

While such close supervision is undeniably helpful in the short term (you’ll certainly progress more quickly if you don’t have to think entirely for yourself), it’s important to note that in the long run, in that marathon trek to professional independence, you cannot simply be a clone of your mentor. What works for them – in research terms, in mentoring terms, in organisational terms, in thought terms – will not automatically work for you, because everybody is different. No two people will do things exactly the same way, and a crucial but usually unwritten aspect of your own training is finding out what works best for you.

Being supervised, being mentored, is about absorbing the things that work for you and politely rejecting the things that don’t. It’s ultimately about finding a path – your own unique path – to professional maturity and independence.

It’s important then to recognise that if your boss imposes their own style too directly, no matter in how benign a fashion, they are ultimately stifling your own growth. Or attempting to turn you into a clone of them. Good mentoring sometimes means saying to your student/postdoc “I don’t agree with you, but go ahead and do it anyway and try to prove me wrong. I don’t think you will, but let’s see”.

It’s both natural and important for a scientist to be influenced by his/her mentors – that’s exactly why you seek such people out. And every independent scientist, no matter how signature their own style, will bear to some extent the imprint of those to whom they were apprenticed (as an undergraduate, Master’s, PhD, and postdoc).

Learn from your mentors, absorb the bits that you find helpful or which chime, and discard the things that don’t. Learn from them directly, and learn from observing them. Be moulded and be shaped by them, but don’t stay in the mould. Step out of it, and make your own.

Originally published on Total Internal Reflection - HERE.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.

Very true, but indeed difficult to achieve from both sides!

Oh, no arguments there! It's an exquisitely delicate balance, and one that has to be determined on a case-by-case basis.