Elena Conti: “We need not only to convey the excitement of making discoveries, but also to make the environment and career path for young scientists more attractive.”

What drew you to your research field?

I was not one of those people who always wanted to be a scientist. In high-school, an inspiring teacher drew me to chemistry, but at that point I also enjoyed creative outlets and I thought perhaps I could put these latter talents to use and train as an architect. However, when crunch time came to make a decision for university, the interest in learning more about chemistry won, eventually leading me to structural biology and biochemistry, and, through a meandrous path, to the molecular machines that regulate RNA metabolism. Now, I try to understand the chemistry that underlies the function of these amazing molecular machines and that is embedded in their structure – deciphering their architecture at the atomic level somehow ended up merging the two paths I was originally torn between.

What do you see as the most important developments in your field in the past ten years?

Electron microscopy introduced seismic waves into the field. Prior to the ‘resolution revolution’, we were dependent on X-ray crystallography to be able to visualize and characterize our proteins. Of course, we could extract many meaningful findings that informed our understanding of RNA metabolism, but the road to success was arduous and fraught with stumbling blocks. One could spend a large amount of time and resources attempting to get diffracting crystals. Electron microscopy all but removed these restrictions and allowed us to see much larger macromolecular complexes, with the added advantage of often capturing different conformational states. More recently, the introduction of artificial intelligence systems like AlphaFold (developed by DeepMind) have further revolutionized our work. We can apply machine learning to predict the likelihood of an interaction between two or more proteins and use that information to interpret cryoEM structures and hone our hypotheses. Altogether, these developments now allow us to focus much more effectively on tackling the big and important questions.

What are some of the challenges in your field right now?

The challenges facing the RNA biology field are multifaceted. From the scientific aspect, capturing and understanding everything we can about messenger ribonucleoproteins (mRNPs) is the next major milestone to be achieved. mRNPs are assemblies of mRNA and proteins that serve to organize the mRNA as it travels from the nucleus to the cytoplasm for translation. Unraveling how mRNP particles are built and how they change through the lifetime of an mRNA will provide important insights to our basic understanding of eukaryotic gene expression. It also has the potential to inform the mechanism, efficacy and efficiency of mRNA-based therapeutics. Turning to a technological aspect, the increased use of machine learning presents a double-edged sword in that we can generate lots of data with the click of a button, but we must also consider how to integrate the sheer volume of data into a usable format from which we can easily discern what is valid. Finally, and this seems to be a system-wide problem at the moment regardless of specific field, namely how to recruit and maintain talented scientists. We need not only to convey the excitement of making discoveries, but also to make the environment and career path for young scientists more attractive.

What do you look for when selecting students and staff for your research group?

When I am approached by a candidate, I first assess their previous experience, whether there is logic in the path they have chosen and whether they can communicate their interests and motivation in the initial correspondence. A letter of enquiry where it is clear that they have copy-pasted from our webpage is an immediate disqualifier. The next level involves assessing reference letters, although in general I find this rather difficult – at times, one has to try and infer what the reference letters do not mention rather than what they explicitly comment on. The next, and decisive, level is the impression during their visit to the lab. Can the candidate articulate their past research project by explaining why they thought it was important and how they approached the problem? Do they know the theoretical background, the practical aspects and the limitations of the methods they used? What is the quality of the data they are presenting and did they consider other interpretations of the results? Importantly, do they handle questions in an honest, straightforward manner? Feigning expertise is another immediate disqualifier, not just for me, but for my entire lab as we collectively carry out the interviews. Naturally, the stage of a person’s education or experience is always taken into account because one does not expect a young student to have the same breadth of knowledge as a post-doc, but I still expect depth. Finally, I look for people that will fit into the dynamic of my group, where critical albeit respectful discussions occur on a daily basis and where the levels of scientific rigour and curiosity, personal determination, and expectations are high.

What roles in the scientific community beyond your own research group have you most enjoyed or see as most important?

One role I enjoy is to co-organize scientific meetings. Discussing with others about the topics and speakers that could inspire and impact the audience is an interesting (and fun) exercise, and is an opportunity to shape the scientific community in many ways. As a female scientist in a senior academic position, I am aware of the responsibility on my shoulders, and I carry it with a sense of pride and joy.

What do you consider to be the most important skills and areas of knowledge for molecular life scientists nowadays?

I think in light of all the artificial intelligence programs that are currently in use and, presumably, many new and improved versions coming down the pipeline, it is critical for molecular life scientists to have some computing and quantitative skills. Yet, this knowledge should not be gained to the detriment of wet lab skills. It is equally important to know how to handle the nucleic acids and proteins at the bench. A grasp of both skill sets would be highly advantageous because not only could each be used to inform the other but it would also provide a more solid and well-rounded foundation with which to obtain and analyze the data.

Introduction to Elena Conti’s work

Research summary

The research group of Elena Conti works to understand the molecular mechanisms at play in major eukaryotic RNA pathways. They use cutting-edge biochemical and structural biology approaches to elucidate the structures of protein–RNA complexes and contextualize the atomic and chemical information in the framework of cellular function and biological significance. Their work spans RNA transport, RNA surveillance and RNA degradation.

Lab webpage: https://www.biochem.mpg.de/conti

Two recent/key papers:

Bonneau, F. et al. (2023) Nuclear mRNPs are compact particles packaged with a network of proteins promoting RNA–RNA interactions. Genes Dev. 37, 505−517. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.350630.123

Schäfer, I.B. et al. (2019) Molecular basis for poly(A) RNP architecture and recognition by the Pan2-Pan3 deadenylase. Cell 177, 1619−1631.e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.013

More information on the EMBO Lecture at the FEBS Congress

Elena Conti will deliver the EMBO Lecture at the 48th FEBS Congress in Milano, Italy on Tuesday 2nd July 2024 on ‘To degrade or not to degrade: molecular mechanisms of RNA homeostasis’: 2024.febscongress.org/

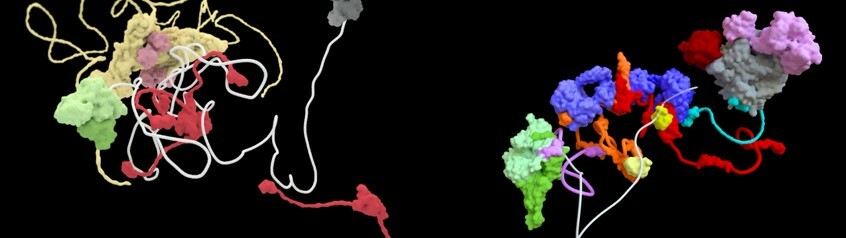

Top image of post: Snapshots from molecular animations of eukaryotic mRNAs (in white) as they are packaged in protein ribonucleoprotein particles during the biogenesis process (left side) juxtaposed to their degradation by the exosome complex during a quality control process (right side). The protein surfaces and interactions were obtained from integrating experimental structural information with predictions from machine learning tools. Credit: Margot Riggi, Janet Iwasa, Elena Conti.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.