We need to reduce the emphasis on first-author papers in academic career progression.

Do you remember writing up science experiments at school? There would be the Aims, the Method, the Results, and the Conclusion, maybe 1-4 figures in total, probably only a single assay, and only a few pages in length at most. Done! Funnily, that’s pretty much how it used to be with research papers (Don’t believe me? Check out this 1986 classic from Tom Pollard).

Things have changed a lot since then. Papers nowadays are like 2-3 of those earlier publications put together (and that’s just the main figures!). They used to be novellas, now they’re “War and Peace” epics, bloated behemothaurs with the turning radius of an oil tanker and the subtlety of an artillery barrage. Such sagas are undoubtedly impressive, undoubtedly a ton of work…but whose work?

With papers getting so engorged and taking so long from conception to publication, it’s often more a matter of luck than ability to have a 1st authorship in your pocket by the time you finish a PhD or postdoc contract. Maybe you started the project and it’s published as a 1st authorship long after you left the group; maybe you came in towards the end but got it over the line and were awarded co-first status. Maybe you supplanted the original first author at some stage in the process.

The problem at the moment is that only 1st and last authorships are seen as quantifiable for career progression in academia – anything in between can be worth a lot or a little but it’s almost impossible to tell exactly how much. Even a 1st authorship input can vary between contributing almost all of the figures for a paper and contributing >50% of the figures.

This system has always generated a bias against technical specialists, who tend to get relegated to the middle of authorship chains because they “only” did the mass spectrometry, or the electron microscopy, or the structure modelling (as I’ve argued previously, having paper credits in the style of film credits might be both fairer and more informative).

These multi-year, multi-project papers undoubtedly benefit last authors more than they do 1st authors. A last author, usually not subject to the same kind of career pressure as the 1st author, can resist publication, continually adding more and more data to the story, in anticipation of the funding benefits that will come from publishing a high-impact paper, while the young scientists doing the work come and go. Of course, these so-called “blockbuster” publications that can result from this approach benefit 1st authors as well, but primarily if the 1st author is lucky enough to publish it before they leave the group.

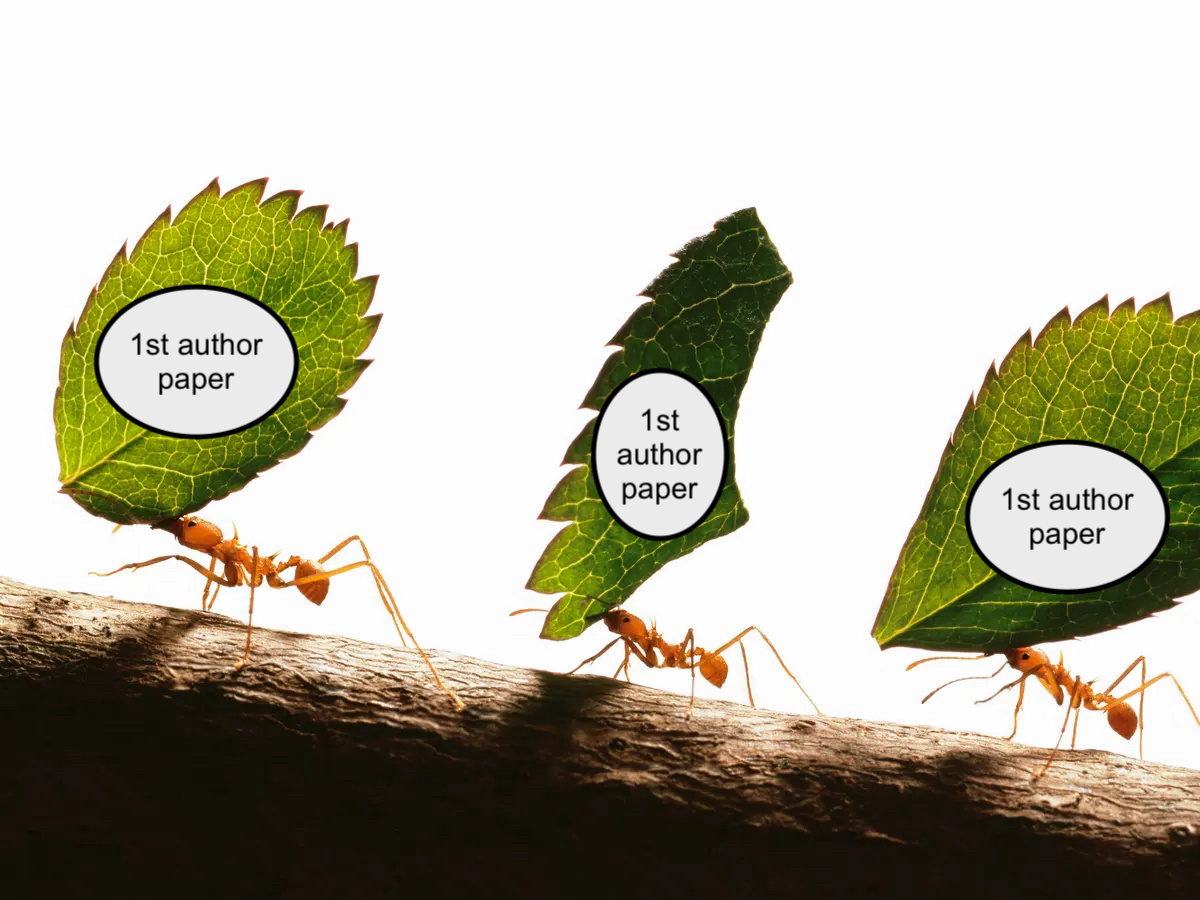

But despite this ludicrous randomness, this lack of agency on the part of its junior contributors, 1st authorships still play an outsize role in academic career progression. A 1st author paper is usually the ticket to a postdoc fellowship, and 1st authorships during a postdoc position can pave the way to high-roller starting grants. Especially when they’re 1st authorships of publications in prestige journals.

Although a return to shorter papers would be welcome, the continued focus on the importance of doing (perceived) high-impact work biases in favour of larger and more sprawling publications, while the peer review of these epics has slowed the publication process to a crawl (As Solomon H. Snyder notes in this excellent commentary, Benjamin Lewis’ vision for scientific publishing when he founded Cell has drifted far from its original moorings).

We all know this. We complain, but we continue to play along, because the rewards – for those lucky enough to get them – are still perceived to be worth the cost, which is why prestige publishing culture remains alive and well despite many words and efforts to highlight its unfairness and rightly questioning the value this culture provides to research itself.

But when the size of papers makes them literally multi-year high-investment projects, it seems unrealistic to insist on 1st authorships as evidence of individual competence and productivity. It’s already becoming more difficult to assess PhD theses because it can be hard to tell how much of the work presented was actually done by the student themselves (especially if it’s a compound thesis consisting of published papers stitched together). Interdisciplinary work and collaboration are good things from a research perspective, but inevitably reduce the percentage contributions from any single author to a research project.

In this climate, it should be enough for young scientists to describe what projects they’ve worked on and what their contributions to those projects were. A valued contribution should be worth more than a rather fortuitous 1st authorship.

In the private sector it’s enough to say that you’ve worked on a project when updating your CV; in academia, we’re basically insisting that young scientists are the first employees of a firm and responsible for taking it all the way to a public listing on the stock market. This is silly. Especially when a description of what project a person has worked on and what they did in it is probably more informative than a citation of a publication where their name is one of many.

Implementing this change would make it easier for young scientists to move from project to project without career penalty (with a likely incidental benefit that extractive and exploitative lab heads would find it harder to retain talent). Insisting on the a 1st author paper at the end of a PhD, though well-meaning, is ultimately a submission to this unsatisfactory and outdated model of academic credit mechanisms, and as the decision to publish always (and correctly) rests with the group leader it deprives young scientists of a certain degree of independence. If you’ve worked 3+ years on a project, and worked hard, you will have data and you will have a story you can tell about it, regardless of whether you have a 1st authorship or not.

Papers used to be the equivalent of lovingly building some kind of garden feature in our backyard, but they’re now like assembling an arch from Stonehenge (and occasionally, the entire circle). That won’t change any time soon. But the charade of insisting that 1st authorships are the only meaningful currency for young scientists needs to go.

Originally published on Total Internal Reflection – here.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.