Adrift in the “Unknome”

As part of World Cancer Day (4th Feb), the journal of Molecular Oncology invited researchers to take part in a writing competition aimed at highlighting the impact of the exposome on cancer risk. This entry, by Katherine Kelly (German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Germany), received an Honourable Mention.

There are two sides to the exposome – the active (like smoking a cigarette), and the passive (like being in the same room as one) – but there is also a gray area – an “Unknome” – made up of things that we choose to do because we don’t know that they harm us. It’s frightening to think of the elements of “Unknome” that continue to occupy our daily lives because their harmful effects haven’t been discovered yet – but what I find more frightening are the substances proven to be dangerous, which persist in the “Unknome” because their risks have not been effectively communicated.

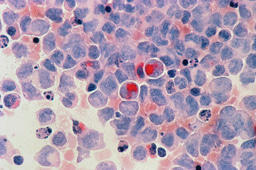

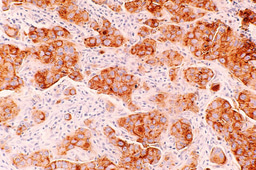

In 2015, following an exhaustive evaluation of over 800 scientific studies, the World Health Organization officially classified processed meat (including ham, bacon, sausages) as a class 1 carcinogen – placing it in the same category as tobacco smoke, asbestos and ionizing radiation, and implying that it is known to cause cancer – particularly colorectal cancer – in humans. Yet little has changed in policy or in public knowledge in the nine years since. Today, many educated people do not even know what constitutes processed meat, not to mention that it is known to cause cancer. In 2024, processed meats even continue to populate hospital menus, without anyone questioning how this can be considered ethical in any institution dedicated to promoting health.

The biological mechanisms behind the meat cancer link are not fully understood. Leading hypotheses center around three major groups of carcinogenic compounds: N-nitrose compounds and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are produced as part of certain meat processing procedures, and heterocyclic aromatic amines, which can be generated during high-temperature cooking. More research into these processes is certainly warranted, however the more pressing need right now is not to acquire further mechanistic insight, but rather to bridge scientific evidence with societal changes.

Think about cigarettes: in most countries smoking is forbidden inside public buildings, tobacco cannot be purchased by minors, and is sold from behind glass barriers, plastered with gruesome visual reminders that it will put your body at risk. The rules make sense for something that we know can kill. Likewise, mothers do not hold cigarettes to their children's mouths. However when red and processed meat were found to be directly linked to the development of cancer, nothing seemed to change. Processed meats continued to appear on supermarket shelves without health warnings or restrictions on their purchase or consumption. These known carcinogens continued to be actively marketed to us as consumers, to be fed to uninformed children in school canteens, and – in what strikes me as a colossal moral contradiction – to cancer patients in hospital meals.

In 2023 scientists from the German Cancer Research Center conducted a simulation study to investigate the potential reductions in CRC (colorectal cancer) incidence and mortality under the optimistic trajectory that processed meat were to be eliminated. Their simulations predicted that eradicating processed meat consumption would prevent almost 220,000 CRC cases in Germany alone over the next thirty years. While these numbers are compelling, it would be unjust to evaluate the overall impact of such a decision in terms of a single outcome, given that meat consumption contributes not only to cancer, but to almost all major causes of death in the developed world. Heart disease, stroke and other cerebrovascular diseases, which are also linked to excessive meat consumption, account for around 25% of deaths in high and middle income countries – more than that of all cancers combined. Moreover, incentives to avoid meat stretch far beyond matters of personal and public health, towards more pressing ethical concerns about the future of our planet and the abhorrent treatment of non-human animals, especially in factory farms.

There must be a moral responsibility among healthcare professionals to ensure that the behavior of their institutions aligns with the current state of knowledge about diseases and their preventable causes. This could mean establishing “meat-free zones” or at least placing health warnings on the harmful foods which they offer. Some hospitals have already taken this initiative. In London, King’s College Hospital has committed to transition to a plant based food environment, and gradually remove processed red meat from its menus. Eleven of New York City’s hospitals have also moved towards serving plant-based meals as the default option.

Humans have complex relationships with food. Food brings people together. For many people, food is home. Moving away from a meat-based diet requires us to let go of familiarity and to recognise that substances we have always considered “normal” are not necessarily good. We are lucky that meat is not something we passively take in through the air, that can be passed from person to person like miasma. It is a voluntary choice that we take with every meal for ourselves or anyone under our care. We have power over the “Unknome” if we choose to take it.

Photo by Pawel Czerwinski on Unsplash

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.