A woman you have never heard of made biochemistry possible

For countless protocols in the life sciences we have to thank a hot summer in 1881 near Dresden (Germany), the insight of an American woman with Dutch heritage, and her husband, who wanted to grow colonies of microbes floating in the air.

Walther Hesse (1846-1911) was trying to grow microbes by adding gelatine to nutrient-rich broth media. But gelatine kept melting in the hot temperatures, turning Walther’s jelly into a liquid glob. Walther’s wife Fanny Angelina Hesse (1850-1934) had an insight that revolutionised the life sciences forever. Why not using agar instead of gelatine?

A never-before-seen portrait of Walther and Fanny Angelina Hesse in Saxony in 1897 (Estate of Dr. Wolfgang Hesse)

Agar has been used for centuries for cooking in many Asian countries and because of her Dutch heritage, Fanny Angelina knew of agar’s use in jellies in colonised Java (present-day Indonesia). Unlike gelatine, agar remains firm despite the constant hot weather and this switch from one cooking ingredient (gelatine) to another (agar) has been a game changer not only for growing microbes, but for the whole life sciences.

Agar and the derivative agarose are today the go-to substances to create gels used in countless protocols. Agarose gel electrophoresis is essential in biochemistry and biotechnology; the microbial plating technique using Petri dishes and agar plates is fundamental to microbiology and molecular biology. How many more protocols use agar and agarose? How many industries need these substances to work?

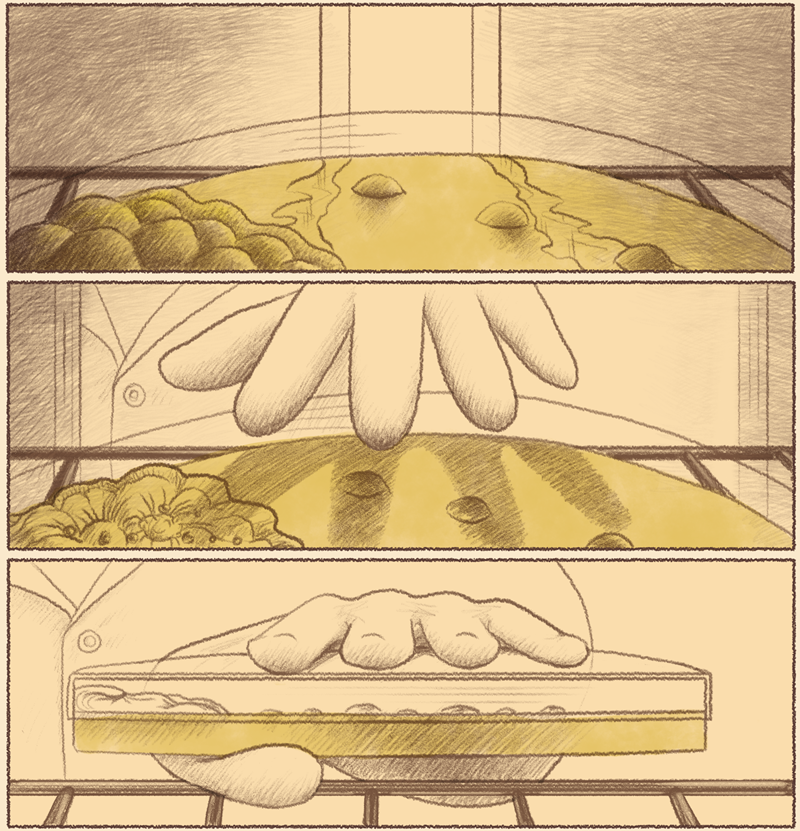

Walther and Fanny Angelina Hesse in their home lab near Dresden (drawing by Dr. Stephanie Herzog/@shog_draws)

So why isn’t Fanny Angelina Hesse a household name, like Julius Petri (1852-1921) after whom Petri dishes are named? For one, Walther and Fanny Angelina Hesse never published a paper describing the use of agar, unlike Julius Petri who described his dishes in 1887. Instead, they notified Robert Koch (1843-1910), with whom Walther had spent a research stay during the winter prior. Agar found its way in the scientific literature through Koch, who mentioned it in his world-famous 1882 lecture describing the cause of tuberculosis. Koch didn’t acknowledge the Hesses for the idea of using agar in growth media for bacteria but, to his credit, in the same paper he expressed how agar, in his opinion, wouldn’t work well. Which of course is not the case, as microbiologists have known for over a century.

A second reason for Fanny Angelina Hesse’s oblivion might be her humbleness. She never spoke of her achievement, even though textbooks started to mention her name during her lifetime. And this too perhaps contributed to a third reason: the fact that there is little information available about her online—until now.

Set out to find more about this story I traced the great-grandchildren living in Germany who shared with me unpublished historical material about Fanny Angelina Hesse. This historical material includes 11 scientific illustrations from 1906, in which Fanny Angelina drew colonies of typhus bacteria on agar plates for her husband’s last publication, family portraits, and an unpublished biography (in German) written by her grandson Wolfgang.

Wolfgang Hesse (1915-2004) presents many touching, personal memories about Fanny Angelina, which perhaps for this reason never made it into the scientific literature. These gave me the idea to create a graphic novel about Fanny Angelina Hesse and the introduction of agar into the life sciences, together with an incredible team of illustrators and scientific advisors. Our project can be supported through Patreon. The story is relevant for all the life sciences, and indeed for everyone! We owe to Fanny Angelina Hesse antibiotics, vaccines, molecular cloning, modern genetics, and so much more.

Hopefully this will contribute to giving due credit to Fanny Angelina Hesse, and you will rejoice encountering again her name in the future. Whatever the case: remember next time you pour an agarose gel that without Fanny Angelina Hesse you might be using gelatine.

A staple in every microbiology lab: agar plates (drawing by Dr. Eliza Wolfson/@eliza_coli)

Corrado Nai is a science writer with a PhD in microbiology. He has written for Smithsonian Magazine, New Scientist, Small Things Considered, The Microbiologist, and many more. He’s currently living in Indonesia with his wife and baby daughter.

References and further reading about Fanny Angelina Hesse:

- Arthur Parker Hitchens & Morris C. Leikind (1939), The introduction of agar-agar into bacteriology, Journal of Bacteriology 37(5):485-93

- Wolfgang Hesse (1992), Walther and Angelina Hesse – early contributions to bacteriology, ASM News 58(8):425-8

- Corrado Nai (2024), Meet the forgotten woman who revolutionized microbiology with a simple kitchen staple, Smithsonian Magazine (25 June 2024)

- Fanny Hesse Graphic Novel website

Top image by Stephanie Herzog.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.