For a bunch of people who are supposed to be really smart, scientists spend a huge amount of time feeling really stupid. Partly it's a Socratic thing - the more you learn, the more you realise how little you know - but it's also because there are few professions more in thrall to the notion of genius.

From Newton to Maxwell to Darwin to Einstein to Crick and branching off in every direction you care to look, every field has its totemic genius, the visionary who saw farther than their peers and laid the foundations for others to build on.

In many cases those contributions are still relevant today, acting as a constant reminder to young scientists of what their forebears achieved. And of course there are many contemporary geniuses (both acclaimed and self-proclaimed) rising seemingly without effort above their earthbound colleagues.

It's all humbug, of course. They work like dogs, every one of them.

Theoreticians probably do a better job of hiding it than experimentalists, but they all graft the same. Subscribers to the American work ethic will let you know that they can work harder than anyone else out there (a deception); subscribers to the British work ethic will tell you they never manage to get any real work done at all (a deception).

The irony is that no matter how hard you work and how smart you are, you can't legislate discovery. You have to be lucky too.

Probably nowhere is this more evident than in the Nobel prizes. The general public probably think that the Nobels are awarded for being a genius; most scientists grumble that the Nobels are awarded for being jammy. Certainly there's a long, long list of acclaimed geniuses who everyone feels should have won a Nobel prize but haven't. There's also an equally long list of Nobel prize-winners who were simply lucky (and smart enough to take advantage of that luck when it came).

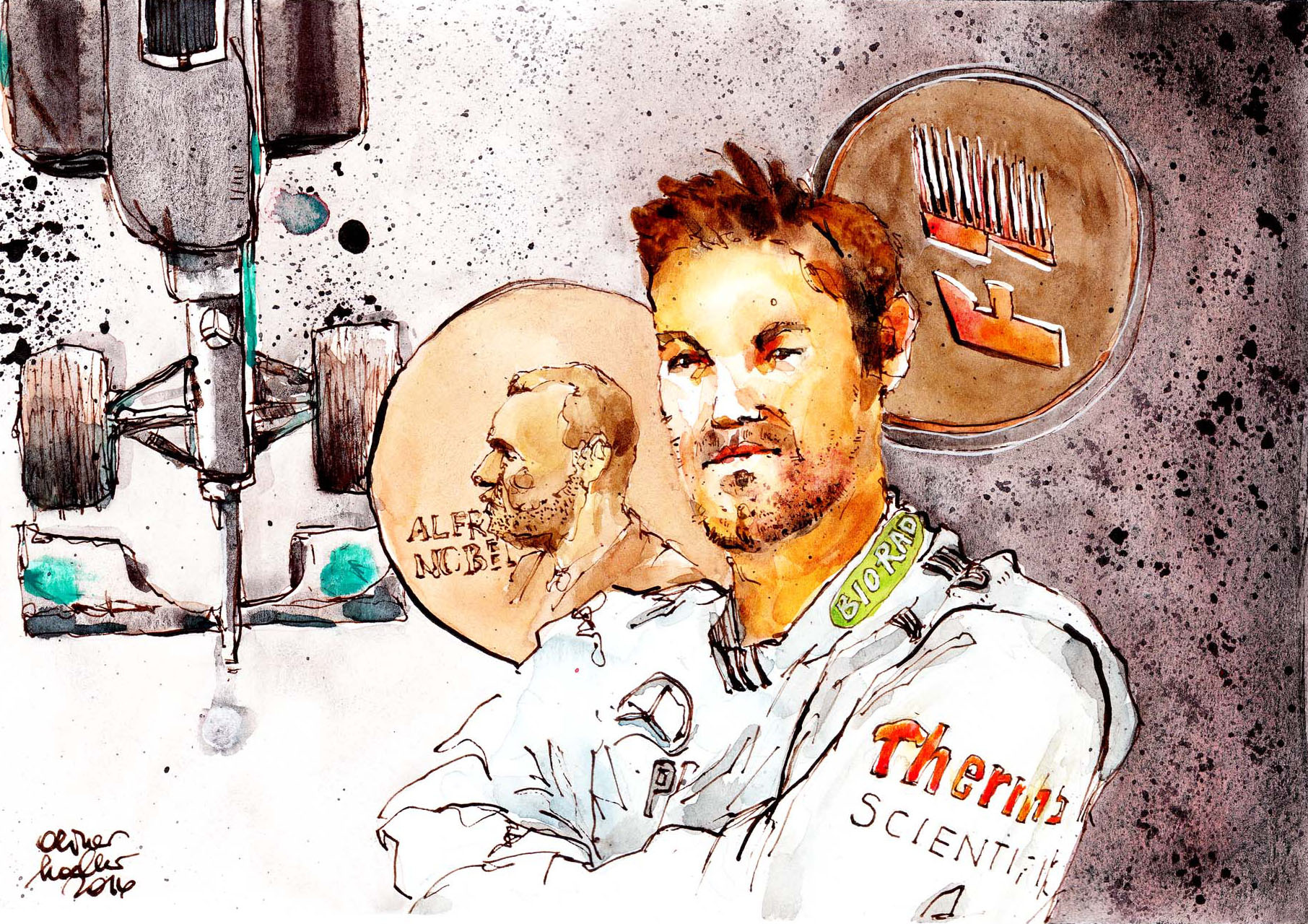

In this sense, there's a strong similarity with the 2016 triumph and subsequent retirement of Formula One champion Nico Rosberg. Rosberg is unlucky to have had as his teammate Lewis Hamilton, a driver widely acclaimed as one of the all-time geniuses behind the wheel of a motor car.

Because Hamilton is a genius and Rosberg isn't, many people felt that Rosberg didn't deserve to be champion. He couldn't win races and dominate weekends in the seemingly effortless style of Hamilton, he had to graft and bank points and rely on luck.

He had to do this while every pundit, commentator, and colleague in the Formula One paddock lined up to say that Hamilton is a better driver than he is. He had to listen to everybody (Hamilton included) say that only mechanical failures cost Hamilton the title that year. And he had to endure this nonstop public criticism for a confidence-crumbling four (four!) years.

But he managed. He won a world title by recognising his luck (having the fastest car on the grid), focusing on his own strengths, persevering, and taking his chance when it came.

And it's here perhaps that Rosberg can provide an unlikely but salutary example for us scientists. We're not all geniuses and we can't all be geniuses, and we'll probably spend most of our careers feeling like we're in geniuses' slipstream, but the big prizes are still within reach. Diligence, determination and, yes, doggedness are what defines a real scientist - even more so than intellect.

Originally posted on Total Internal Reflection - HERE

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.