Is science losing its playfulness?

Aaron Klug, a former director of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK, was once asked in an interview what the secret was behind its success. This one institute had won more Nobel prizes than many countries (and continues to win them, most recently with Greg Winter in 2018), so what was the blueprint, asked the interviewer, for this Nobel factory?

Klug took umbrage at the analogy. The LMB isn’t a factory, he insisted, but a garden. You can’t legislate discovery, and you can’t manufacture success. You need an environment in which ideas and techniques can be nurtured, tested, refined, and brought to fruition.

While comparing something to a garden might sound like a rather wet analogy (excuse the pun), and almost inevitably invites the ungenerous mind to make a number of unflattering comparisons – some people’s idea of a garden is more like a sugar cane plantation / some plants grow best when heaped high with manure etc – Klug’s essential point is accurate. By definition, a nurturing environment in which younglings can be protected but stimulated is almost certainly best.

And it’s not just plants. Animals too flourish under such conditions. Playtime is an essential part of many young creatures’ growth, and nature documentaries abound with scenes of lion cubs playfighting, fauns running and leaping, and monkeys sticking their fingers in each others’ eyes and orifices.

Playtime helps develop skills that the juvenile may later find essential in adult life. Similarly, one can argue that sports and games are more than just a means of exercising and socialising, but also represent a way of preserving and practising skills that can be put to more essential use elsewhere: teamwork, decision-making under pressure, courage, sang-froid, timing, and more.

It should never be forgotten that the lab, the research group, is a learning environment too; indeed, in its best incarnations a laboratory is a learning environment for all its members, no matter what degree of seniority they hold. Regardless of how metronomically a lab may churn out research papers, it functions best when it is focused around the development of the people within it. The art critic Ernst Gombrich once opined that there is no such thing as art, there are only artists – and it’s a motto that lab heads would do well to enact.

If a lab focuses on producing good scientists, then the science it produces is almost always likely to be good; if a lab is consumed solely by the idea of producing good science, then its output and its reputation is much less certain. It is notable that in the obituaries of Ben Barres and Günter Blobel, and the unusual level of collective sadness that their deaths triggered in the wider scientific community, reflected their extraordinary abilities as mentors as much as their prowess at research.

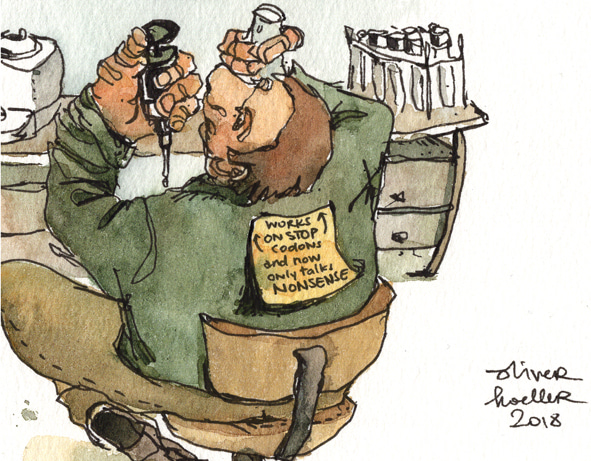

And if a lab is to be an effective learning environment, if it is to capture that spirit of playfulness, then it should above all embody a sense of fun. Anecdotes abound about the early days of molecular biology – pranks, quips, practical jokes, and bizarre experiments done simply out of devilment. Naturally, to some extent this reflects the Corinthian spirit of the age in all its pros and cons, and there is no doubt that research has gained enormously in both output and equality by the greater professionalism of more recent decades. But at the same time there is a nagging sense that that same establishment of oversight, accountability, and professional standards have often come at a terrible cost: joylessness.

Science, fundamentally, is a creative activity, and as such it requires the kind of atmosphere that one usually encounters in a theatre rehearsal – people being empowered and encouraged to take risks, to follow their intuitions, to try new things and test their limits, and to be unafraid of failing. You can, and should, always challenge people to do better, but you can seldom bully them into improving.

The best and most original science, like cooking, often comes from novel combinations of flavours, not by churning out tray after tray of TV dinners. Any chef will tell you that the secret to any dish is the quality of its ingredients, and you can bet that the best come from a garden, not a factory.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.