Self-regulated learning (SRL) is an essential skill for any graduate to master, but especially a student of the biosciences. The volume of information a bioscience student is expected to manage, and the complex analytical skills we expect of our graduates, requires the ability to manage one’s own learning effectively.

The previous blog in this series of three focused on the process of SRL and how our learning and teaching activities can support its development. In parallel with the learning environment, the assessment environment also needs to be aligned with this goal of developing SRL. The assessment regime that the student experiences is particularly significant in how they approach self-regulation, and in turn is strongly impacted by the learner’s ability to self-regulate. This blog aims to suggest ways in which assessment can support the development of SRL skills in undergraduate students.

A major element of SRL is the ability to judge one’s own progress and performance, so assessment (and an effective feedback process associated with assessment) can be a powerful factor in SRL development. The task here is how to challenge learners with assessments that both develop their SRL, but also evaluate their progress. The balance of formative and summative assessments is a significant issue in this regard.

Assessment IS learning

For many years, there has been a movement towards ensuring that assessment and feedback information support the learning process, rather than just evaluating students’ abilities or knowledge. Central to this idea that assessment is learning, is Biggs’s (1996) concept of constructive alignment (see also Biggs and Tang, 2011; Biggs, 2014), that the assessment of a course should be informed by, and enable demonstration of, the intended learning outcomes and the teaching and learning methods the learner undertakes. However, there is more nuance to this model, as one can consider assessment as being of learning (assessment that tests learning outcomes and competence), assessment for learning (assessment that enables learners to benchmark their progress and drives the learning), and assessment as learning (assessment that delivers part of a curriculum, and/or develops a student’s abilities) (Rutherford et al., 2025).

Thinking of assessment in terms of its ability to support learning is majorly beneficial to learner development. This concept of assessment and feedback is also important for the development of SRL. Rather than focusing assessment solely on whether the learner has achieved mastery of a concept or a skill, we can also focus assessment on supporting the learner in reflecting on how they have achieved that mastery, and whether their learning strategies are working (Schneider & Preckel, 2017).

Designing assessments and feedback to support SRL

Designing assessments to support SRL requires a paradigm shift in how we think of and design assessments. In many cases in HE, the process of design for a course or module is focused on what content needs to be delivered, or what knowledge base is required at the end. This approach, proven through centuries of HE practice, is effective, however, it is potentially limiting in developing the learner as a learner, and fostering independence. In particular, in an age where information is democratised and freely available, the focus on remembering knowledge is perhaps too limiting (Brabazon, 2007). A focus on how learners acquire, evaluate, understand, and apply knowledge is arguably of equal or more importance.

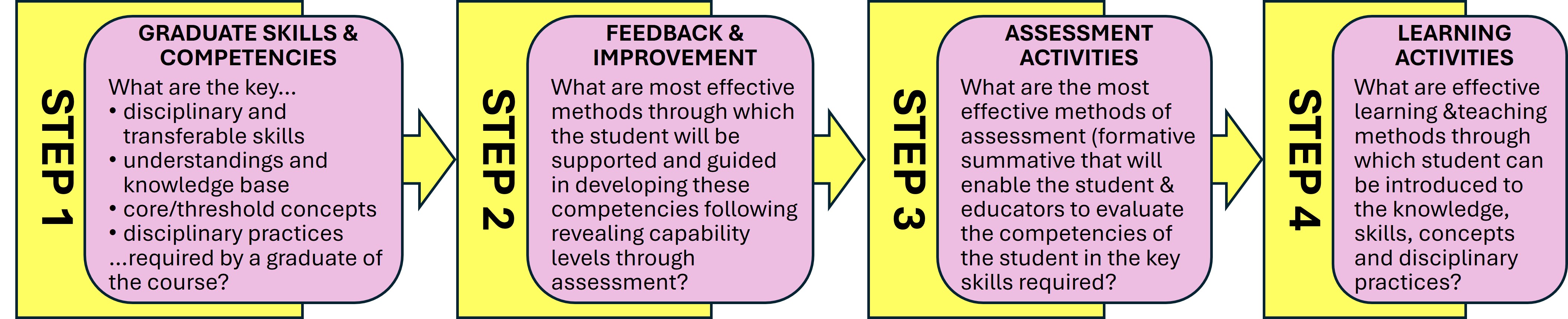

Designing assessments to support SRL and other skills needs to begin with the skill outcome, rather than the knowledge (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005), as summarised in figure 1. The first consideration should be the course/programme learning outcomes – what does a graduate of this course look like in terms of their skills and abilities (rather than factual content)? For example, the ability to critique information, to plan and design experiments, to analyse data, to communicate effectively and concisely, or to evaluate sources in the literature. Then, what guidance and support (teaching and feedback) do they need to get them to demonstrate those skills? What assessments would help them develop and demonstrate those skills and competencies? What subject content would enable them to show these skills and understandings? Finally, what would be the best way to deliver this content to them – should it be teacher-led (didactic) or learner-led (inquiry-based)? Assessment that supports the students in developing skills, using knowledge to underpin the use of those skills, reflecting on the process and (most importantly) identifying how to improve, is an impactful activity (van Merrienboer et al., 2019).

Figure 1

Figure 1 – The ‘backwards’ design of a curriculum. Successive steps of effective curriculum design embedding constructive alignment. Key graduate outcomes are defined, before feedback and improvement, which then informs the assessment strategy that can demonstrate competence in the outcomes, which then informs the ideal learning and teaching activities that best support development of the outcomes.

The impact of effective feedback on SRL development

Assessment is not the only factor in this process. For assessment to truly impact SRL, it needs to be paired with effective and supportive feedback processes as well. Feedback on a learner’s performance is essential if they are to judge the efficacy of their SRL skills, and their progress as a learner or practitioner in that discipline. Key to this feedback process being effective is that it needs to be learner-focused (Henderson et al., 2019), centred on the performance of the learner and what they need to do to improve, rather than focused overmuch on the outcome of the assessment alone. However, students need to be supported in their engagement with the feedback process for it to have an impact (Winstone et al., 2016).

The following sections each focus on suggestions for assessment and/or feedback approaches which would support the development of one of the domains of SRL. Each section will suggest possible assessments that could support these, in addition to feedback approaches that would facilitate that dimension’s development.

Assessment and feedback to support cognition

Assessment that supports the development of thinking and information processing activities could function largely on application of knowledge and using factual content to solve problems and challenges. Open Book Exams are an example of this (Brown et al., 2004; Villaroel et al., 2020), where students are allowed to bring study materials into an examination, but the questions focus not on factual recall, but on finding a solution to a scenario; or applying the information to solving a problem; or designing a research strategy to answer a particular issue. This assessment format is only effective if two conditions are met: a) The questions are appropriate to the open book format, and don’t encourage students to merely ‘mind-dump’ information from their classes; b) That the students are taught in a manner which encourages them to apply knowledge rather than just remember it.

Another assessment approach would be to utilise the concept of ‘retrieval practice’ (Higgins, et al., 2024; Burgess, 2024) and provide regular, light-touch, formative assessments for students to gauge their progress and reinforce information. Retrieval Practice has been shown to enhance student retention of information and understanding. Although it focuses more on factual recall, it can also be applied to the development of understanding and problem-solving, and can support students in developing cognitive strategies.

Feedback processes that best support cognition would potentially include methods that encourage students to reflect on their performance and identify skills gaps that they need to address. Most important with this would be putting a clear strategy in place to address those skills gaps, and to improve (Winstone and Carless, 2019). Identifying areas where they are strong or lacking can be the key to applying metacognitive concepts to evaluate their learning efficiency.

Assessment and feedback to support metacognition

Assessments that support metacognition would be ones which focused on process rather than the product of an activity (Smith and Francis, 2024). For example, focusing an assessment of a report-writing task on getting the students to log why they decided to present a particular piece of evidence in the results section, or why one reference was appropriate for the introduction, while another was of less use. Evaluating the students’ understanding of the writing process and aims of each element of a report, and their ability to self-critique their work, would support metacognitive elements.

Another approach would be to encourage students to work collaboratively to prepare for an assessment or exam. Encouraging them to share revision tips, to test each other, and to work collaboratively to peer-teach each other, or develop resources, encourages learners to think about the process of learning, and what works (and, importantly, what doesn’t work) for them.

Arguably, all feedback information should support metacognitive domains of SRL. Feedback information should encourage a student to question their learning approaches, and identify ways of improving them. In this space, feedback as dialogue is very powerful (Nicol, 2010). Asking a student to reflect on why they approached the assessment the way they did, or what choices they made. Encouraging students to identify things they thought worked well, and those that did not. Feedback that asks questions, rather than providing answers, is the key here. Active feedback that requires engagement by the student, and encourages dialogue with peers and educators, is fundamental to supporting metacognitive development.

Assessment and feedback to enhance motivation

One of the best ways to develop motivation through assessment is to present assessments in which the learners can see a vested interest, or a personal connection. ‘Authentic’ assessments, aligned to scenarios that students might face in the world of work, are particularly powerful (Ajjawi et al., 2023). Utilising examples or scenarios from real situations, framing assessments around real cases or actual problems from industrial partners, can be excellent ways of helping students identify what best motivates them to learn. Equally, assessments in which the students have an element of choice (either in the subject matter of the assessment or the medium of the assessment) has a strong impact on enabling them to identify elements that motivate their learning (Rutherford et al., 2024).

Feedback to enhance motivation does not necessarily need to be feedback that praises and encourages the student. Motivational theory (Bandhu et al., 2024) identifies many forms of motivation besides the more common intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Feedback that encourages actualisation motivation (motivation to fulfil one's potential and achieve personal growth (Winstone et al., 2016) or introjected motivation (motivation induced by a failure to achieve a goal (Bieg et al., 2024), can also be powerful motivators, provided that they offer a scaffold for the student to help themselves and develop strategies for improvement. The essential element of feedback in this space is feedback that encourages students to set both realistic and ambitious goals to achieve in their future learning.

Assessment and feedback to support co- and shared-regulation

Co-regulation is strengthened by good interactions between a learner and their academic mentor or educator. Setting assessments that encourage learner-educator dialogue is important here (Er et al., 2020). Traditionally, educators have stepped back from the assessment process, requiring students to develop their assessment outputs alone. However, there is potential for academics to support students in their assessments, if we see assessment as a learning activity. For example, being actively involved with a student as they draft sections of a report, or encouraging, in a non-judgemental way, to explain the rationale behind their thinking when planning an experiment. This is particularly important in the early stages of an assessment or assignment, where students may need more guidance. Utilising a framework such as the EAT Framework (Evans, 2016; Rutherford et al., 2025) is a way of maximising the support frameworks for assessments, without also compromising the independence of the students.

Socially-shared regulation, requires effective peer-peer interactions in order to develop. Activities which encourage peer-based discussion and reflection on these interactions are, therefore, potentially powerful. Properly structured team-based assessment tasks, which encourage collaborative learning, are key to developing socially-shared regulation of learning. Properly scaffolded, structured, and (most importantly) guided and supported, team activities can support learners in developing the interpersonal skills needed for effective shared regulation (Mendo-Lázaro et al., 2018). For team-based activities to work effectively in the development of SRL, there needs to be both active guidance and support from educators, and also an ongoing element of reflection on the team-based process by the learners (team members) themselves. This is developed more in Francis et al. (2025) and in a recent FEBS blog on teamwork assignments (Pritchard et al., 2025)

Feedback information that involves or encourages learner-educator dialogue is beneficial to supporting co-regulation skills. However, where this is most powerful is when the learner is encouraged to think actively on the feedback information that they feel they would benefit from most, and to use the educator as a resource bank for development, and not relax into a passive role as a feedback recipient. Encouraging learners to reflect on their own potential strengths and weaknesses, and to ask for specific guidance, is a powerful medium for this.

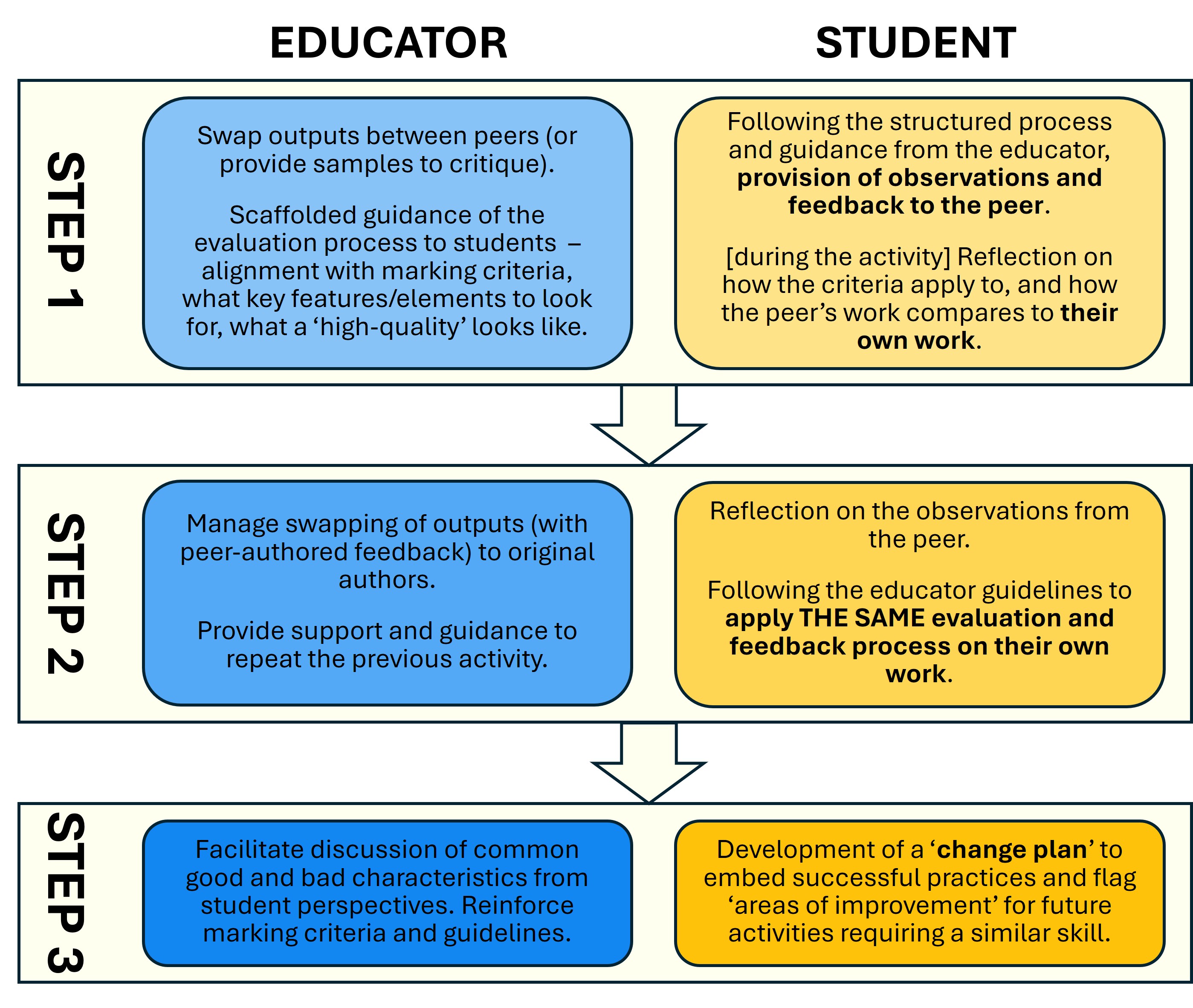

Facilitated peer-feedback activities are potentially powerful in supporting the development of shared-regulation skills, as well as self-regulation. Peer feedback, however, is often used poorly, merely as a means for students to receive feedback from their peers. This is of limited use to a student, for whom feedback from an expert may be more effective (and is usually more welcome) (van Blankenstein et al., 2024). The true benefit of peer feedback lies in the process of supporting the learner’s self-feedback skills, and using the act of reviewing the work of their peers as a medium for developing their own self-critical skills. A suggested process for this, taken from Rutherford et al. (2025) is included in Figure 2. The process of peer feedback is a facilitated one, with the educator guiding the learners through the feedback process. Then the important step is the last stage, where the individuals use the experience of providing feedback information to their peer, to provide the same critique to themselves. This process not only encourages students to interact socially in an effective way, but also to utilise the effects of that social interaction for their own learning gain.

Figure 2

It is important that both team-based assessments and peer-feedback activities are supported and scaffolded by educators (Francis et al., 2025 and Rutherford et al., 2025, respectively). Without this scaffolding and ongoing support, the learners are unlikely to perceive the educational benefits of the activity, and the teams are less likely to function effectively.

What resources are available to support SRL through assessment and feedback?

A recent EU Erasmus+ funded project (‘EAT-Erasmus: https://EAT-Erasmus.org) has a range of resources around assessment and the support of SRL through assessment and feedback practices, including an extensive report on self-regulation in assessment (Evans et al., 2020).

More substantively, the development of SRL can be supported by the effective use of Generative AI opportunities (Xu et al., 2025). The next partner blog in this series of three focuses on that rapidly-developing set of opportunities.

The development of SRL is fundamental to learner development in HE, and beyond, as our students graduate and become ‘lifelong learners’. We need not only to develop teaching activities that help learners develop these skills, but also to utilise assessment and feedback actively to support them, and take assessment beyond an auditing activity of student learning, to an active and central part of the learning process.

The third blog in this series will focus on ways in which Generative AI can support the development of SRL.

References

Ajjawi, R., Tai, J., Dollinger, M., Dawson, P., Boud, D., & Bearman, M. (2023). From authentic assessment to authenticity in assessment: broadening perspectives. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(4), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2271193

Bandhu, D., Mohan, M.M., Nittala, N. A. P., Jadhav, P., Bhadauria, A., & Saxena, K.K. (2024). Theories of motivation: A comprehensive analysis of human behavior drivers, Acta Psychologica, 244, 104177, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104177.

Bieg, S., Thomas, A., Spreitzer, C., & Müller, F. (2024). Exploring the Complexity of Introjected Regulation in Self-Determination Theory. Int J Teach Learn, 103. https://doi.org/10.47991/2024/IJTLS-125

Biggs, J. B. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment, Higher Education, 32, 1–18.

Biggs, J. (2014). Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 1, 5–22.

Biggs, J. B., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university (4th ed.). Open University Press.

Brabazon, T. (2007). The University of Google: Education in the (Post) Information Age. Abingdon, Routledge.

Brown, S., Race, P., & Smith, B. (2004). 500 Tips on Assessment (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203307359

Burgess, K. 2024. Why we should test our students more. [Online]. WONKHE: WONKHE. Available at: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/why-we-should-test-our-students-more/

Er, E., Dimitriadis, Y., & Gašević, D. (2020). A collaborative learning approach to dialogic peer feedback: a theoretical framework. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(4), 586–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1786497

Evans, C. (2016). Enhancing assessment feedback practice in higher education: The EAT framework. Southampton, UK: University of Southampton. Available at: https://inclusivehe.org/inclusive-assessment/

Francis, N., Pritchard, C., Prytherch, Z., & Rutherford, S. (2025). Making teamwork work: enhancing teamwork and assessment in higher education. FEBS Open Bio, 15(1), 35-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/2211-5463.13936

Henderson, M., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., Dawson, P., Molloy, E., & Mahoney, P. (2019). Conditions that enable effective feedback. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(7), 1401–1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1657807

Higgins, T., Dudley, E., Bodger, O., Newton, P., & Francis, N. (2024). Embedding retrieval practice in undergraduate biochemistry teaching using PeerWise. Biochem Mol Biol Educ, 52(2),156-164. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.21799

Mendo-Lázaro, S., León-Del-Barco, B., Felipe-Castaño, E., Polo-Del-Río, M., & Iglesias-Gallego, D. (2018). Cooperative Team Learning and the Development of Social Skills in Higher Education: The Variables Involved. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01536.

Nicol, D. (2010). From monologue to dialogue: Improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 501–517.

Pritchard, C., Rutherford, S., Francis, N., & Prytherch, Z. (2025) Making teamwork work: enhancing collaboration and assessment in higher education. FEBS Network Education Blog Post: Available at: https://network.febs.org/posts/making-teamwork-work-enhancing-collaboration-and-assessment-in-higher-education?channel_id=724-educator

Rutherford, S., Pritchard, C., & Francis, N. J. (2025). Assessment IS learning: developing a student‐centred approach for assessment in higher education. FEBS Open Bio, 15(1), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.1002/2211-5463.13921

Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychol Bull, 143(6), 565-600. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000098

Smith, D. P., & Francis N. J. (2024). Process Not Product in the Written Assessment. In: Beckingham S, Lawrence J, Powell S, Hartley P, editors Using Generative AI Effectively in Higher Education. 1st ed. London: Routledge. p. 115–26. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003482918

van Blankenstein, F. M., Dirkx, K. J. H., & de Bruycker, N. M. F. (2024). Ask your peer! How requests for peer feedback affect peer feedback responses. Educational Research and Evaluation, 30(1–2), 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2024.2376832

van Merrienboer, J. J. G., & de Bruin, A. B. H. (2019). Cue-based facilitation of self-regulated learning: A discussion of multidisciplinary innovations and technologies. Computers in Education, 100, 384-391.

Villaroel, V., Boud, D., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., & Bruna, C. (2020). Using principles of authentic assessment to redesign written examinations and tests. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 57(1), 38-49.

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Winstone, N. E., & Carless, D. (2019). Designing effective feedback processes in higher education: A learning-focused approach. London: Routledge.

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., & Parker, M. (2016). ‘It’d be useful, but I wouldn’t use it’: barriers to university students’ feedback seeking and recipience. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 2026–2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032

Xu, X., Qiao, L., Cheng, N., Liu, H., & Zhao, W. (2025). Enhancing self-regulated learning and learning experience in generative AI environments: The critical role of metacognitive support. British Journal of Educational Technology, 00, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13599

Photo credit: Pexels | Vlada Karpovich

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.