Scientists who don’t rush to embrace new techniques and assays risk an uphill struggle to win funding.

Like the managers of sports teams, scientists must strive to generate and maintain a sense of excitement about their research programmes. A crucial element of running an exciting (note deliberate avoidance of the word “successful”) sports team is making signings for the upcoming season and showing old players the door. An unchanging squad gives fans nothing to chew over or look forward to.

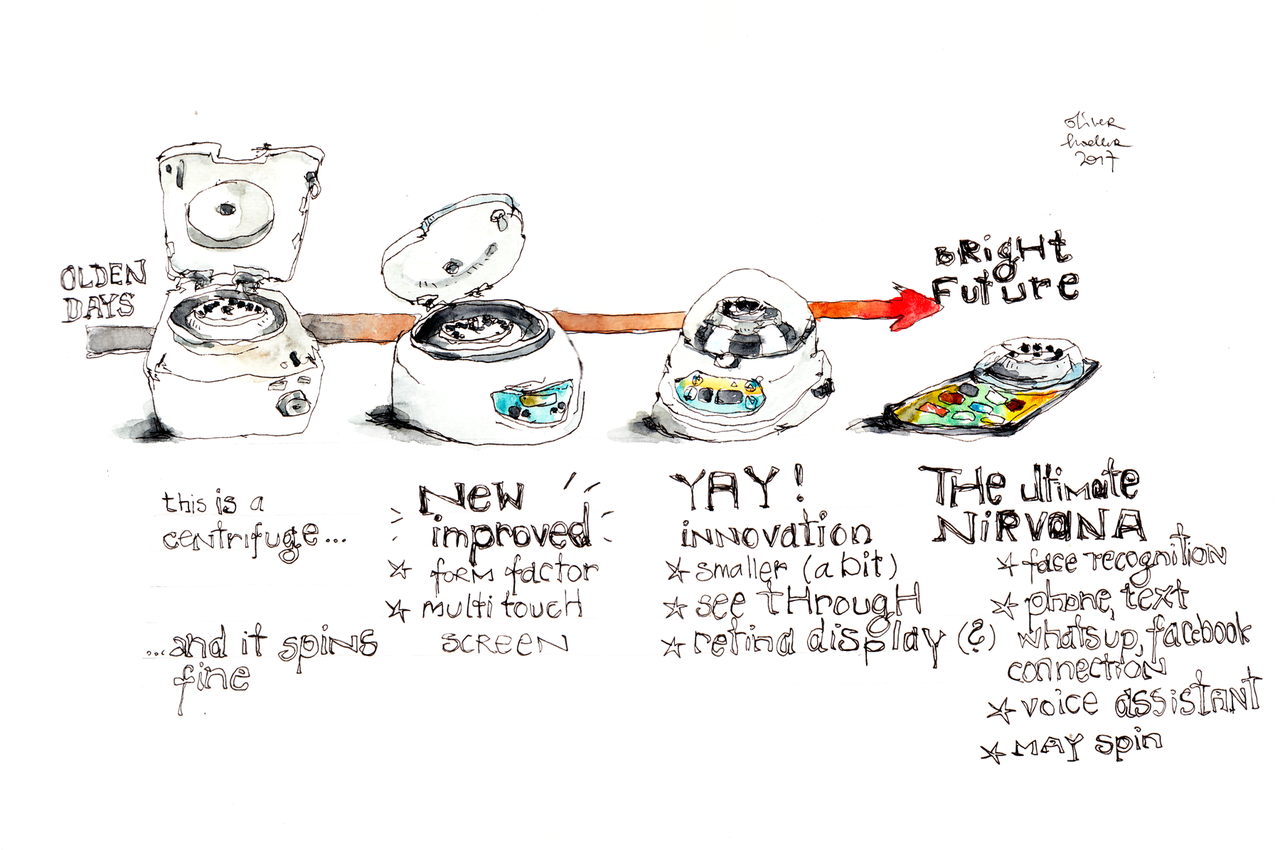

Similarly, scientists seeking to win funding for their research must communicate that they are at the cutting edge of their field. In practice, this translates into the mantra: New techniques! New assays! State of the art! Novelty of approach is the name of the game. It is not enough, or at least not in the current funding climate, to say you are going to keep on doing what you’ve been doing before, and make sure you’ll do a good job.

Why is that, and is it right?

One reason for offering a parade of methodologies is that it creates an impression of dynamism. Simply continuing with what you’re doing reads a bit flat, while cutting-edge techniques, new assays, and new analysis tools give a sense of the future coming nearer. Contrast that with sticking to tried and tested techniques that are well-optimised, have been working for years, and unlikely to throw up surprises. Something that’s shiny may take a long time to optimise, but it’s the very shininess of the thing that’s important.

In sports, that need to keep developing the squad serves two purposes. First, it generates excitement and talking points among fans, which translates into stronger support on matchday; second, it maintains a competitive edge against other teams, who will not be sitting still if they have the resources to advance. It is simply not possible to stay put, because your players will be ageing and other teams will be trying to get an edge on you.

The picture is somewhat more complicated in science. The “fans” here are the grant reviewers, tasked with assessing whether the proposal should be recommended for funding or not. Will they be excited by the proposal, or will they be lukewarm? As with sport, generating excitement translates into stronger support.

The analogy gets complicated when you start thinking about the other teams. Funding in science is competitive, and scientific groups often compete with one another in terms of their research output, but they don’t necessarily directly compete with one another for funding. If a particular research field is having its moment in the sun, then all groups working in that area can be expected to reap the benefits; if a research area is in the doldrums, then all groups will be struggling for funding.

The obsession with new technology may primarily reflect the extent to which scientific advances are driven by methodological advances. A new technique comes along, and then people rush to apply it to whatever it was they were working on before. This approach works well because generally people know what they want to work on, and then have to write a proposal explaining why they think it’s worthwhile.

But the state of the art can be psychological as well as methodological.

It’s far easier to use new technology than it is to come up with new ways of looking at old problems. It’s rare for somebody to question the value of using a new assay/method to look at something, even if the gain in scientific resolution is minuscule; conversely, it’s common for people to question the assumptions underlying a new hypothesis, despite the fact that information will be gained regardless of whether it’s disproved or not.

There are quite possibly bigger conceptual gains to be made from venturing into the unknown, where the need for sophisticated methodology is less acute as so little is already known (think about the incredible advances made in the early days of molecular biology using equipment that’s primitive by modern standards, think of CRISPR’s unlikely genesis). But by sticking to well-worn and well-furrowed research paths, there’s an absolute necessity to be at the cutting edge to avoid being left behind, because there’s comparatively little left to discover.

However in today’s risk-averse, time-limited world of research it’s arguably easier to train a new device on an old problem than it is to invest the time to come up with new ideas.

Originally published on Total Internal Reflection - here.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.