“The Honest Broker” and what scientists can learn from it (part 2)

This post was written by Corrado Nai and Paul Cos and originally shared in the #TheCulturePlate section of the #FEMSmicroBlog, the blog from the Federation of European Microbiological Societies.

of Science in Policy and Politics”

by Roger A. Pielke, Jr (2007),

Cambridge University Press

In this second (and final) installment, we continue presenting “The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics” by Roger A. Pielke, Jr an introduction and field guide for researchers who think: I want to contribute to policymaking; but how? Corrado Nai and Paul Cos present in this #FEMSmicroBlog entry what researchers can learn from the book – and possibly even how they can become an “Honest Broker.”

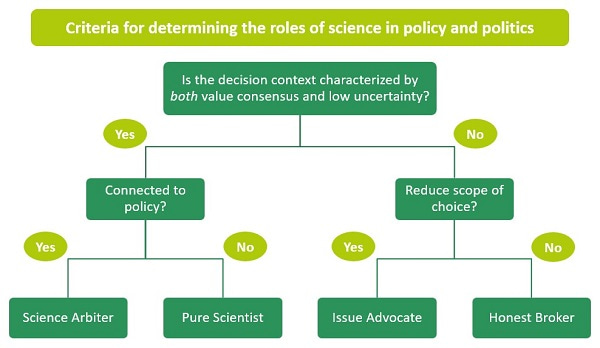

In part one we saw how scientists can take over one of the four (idealized) roles during the process of policymaking, as well as the role of science in democracy.

This part will cover the topics of values, uncertainty, and suggest some ways in which scientists can get involved.

Values, uncertainty, and why it can be messy

The purpose of decision-making is to reduce uncertainty about the future in a preferred direction, and thus to make the “right” choice. Scientists can (and should) certainly help. If things seem relatively straightforward, it is actually messier than that. It all depends on the topic itself, and more precisely it has to do with values and uncertainties – the values that persons, be they scientists, policymakers, politicians, members of the public, share (or not) with other persons, and the uncertainties relative to an outcome.

If aspects additional to science are factored in a certain topic (be it religion, worldview, cultural differences), then values might not be shared among stakeholders. It is very unlikely that scientific facts alone can create a value consensus.

Similarly, even with a value consensus, the outcome of a decision might be uncertain. There is the need for more scientific results, for example; or the behaviour of the public might be difficult to predict. The two extreme examples the books bring are “Abortion politic” (unshared value, high uncertainty) and “Tornado politic” (shared value, low uncertainty). In general, things are quite straightforward when there is value consensus and low uncertainty, which is not often the case. Diagram 1 helps navigate the role a scientists might take.

To make matters even more complicated, often in policy there are no simple choices, and not taking a choice is in itself not an option. Scientists and policymakers are very busy, priorities between scientists and policymakers might be different, and the time frames within which both parties need to operate might be fairly different.

So what?

Uncertainty is not always a disadvantage. For example, uncertainty might spur interest in knowing more about a certain topic, in seeking out more choices between a “yes-or-no” choice, or might carry (secondary) positive effects. As Dwight D. Eisenhower put it: “If a problem cannot be solved, enlarge it.” Scientists who wish to get involved in policymaking need to know, as the author puts it, that “science, well used, holds great potential to improve life on earth. Science, poorly used, can lead to political gridlock, bad decisions, and threatens the sustainability of the scientific enterprise.” Seeking to expand options that a policymaker has, based on scientific fact, seems to be a great way by which scientists can put their knowledge and expertise at the service of society.

The book “The Honest Broker” by Roger A. Pielke Jr brings many detailed examples which help scientist make sense of science in policy and politics. A bullet point summary of the book can be as following:

- Political context shapes the role of information in policy and politics

- There is a role for an “excess of objectivity” of science in political debate

- There is a profound difference between seeking to reduce and seeking to expand policy choices

- The linear model of science policy has profound consequences

- Institutions matter

- It is critical to distinguish scientific results from their policy significance

- Any discussion about science in policy and politics is grounded in visions of democracy

The author also notes that “Honest Brokerage” is challenging for any individual, but is likely to be effective if offered through authoritative bodies such as international panels, professional societies, or national academies. “Institutions can bring together people with different backgrounds and perspectives to provide a spectrum of options,” says the author.

At FEMS, we are learning and want to listen, both on topics related to “Science for Policy” and to “Policy for Science.” We believe that Early Career Scientists face more and more challenges, and FEMS wants to support them though many instruments, including our Grants and Awards schemes. What policy changes could help them (and science, in general)? How to make sense of ever complex scientific results? How to communicate properly with each other?

With difficult questions, no easy answers come. The will to be a “Honest Broker”, or to get involved in the dialogue between scientists and policymakers knowing the issues, the limits, and the capabilities of each party involved, is already a great start.

Top image by FEMS-Eliza-Wolfson-CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.