Science for Policy: The competences researchers need to succeed

This post was written by Julian KEIMER, with many thanks to Lene Topp and Florian Schwendinger on whose work this article is based.

- The challenge: Policymaking questions are increasingly complex and interconnected, e.g., climate change, digitalisation, health, demography, geopolitics. To understand these fields and make effective policies in them, policymakers need science and scientists providing targeted, useful advice.

- The problem: Policymakers and researchers often don’t collaborate in the most productive way to achieve an optimal policy result.

- The solution: Competence frameworks to identify the (missing) cross-disciplinary and cross-policy skills, knowledge and attitudes empower policymakers and researchers to better address today’s challenges.

In recent years, policymaking has seen a rapid transformation of the world it tries to act upon due to the fast-paced technological advancements, climate change, a changing global political situation, and significant societal changes accompanied by evolving expectations from citizens. Institutions that create policy, such as the European Commission, are compelled to perpetually develop their policymaking methods.

In the face of these rapid global changes, the European Commission Joint Research Centre has developed two comprehensive competence frameworks to bolster the skills, attitudes and knowledge needed for effective evidence-informed policymaking.

Having the right competences for policymaking

The first framework, 'Innovative Policymaking', provides guidance for policymakers – from desk officers to politicians – across the policy cycle. It outlines 36 competences distributed across seven clusters: advise the political level, innovate, work with evidence, be futures literate, engage with citizens and stakeholders, collaborate, and communicate.

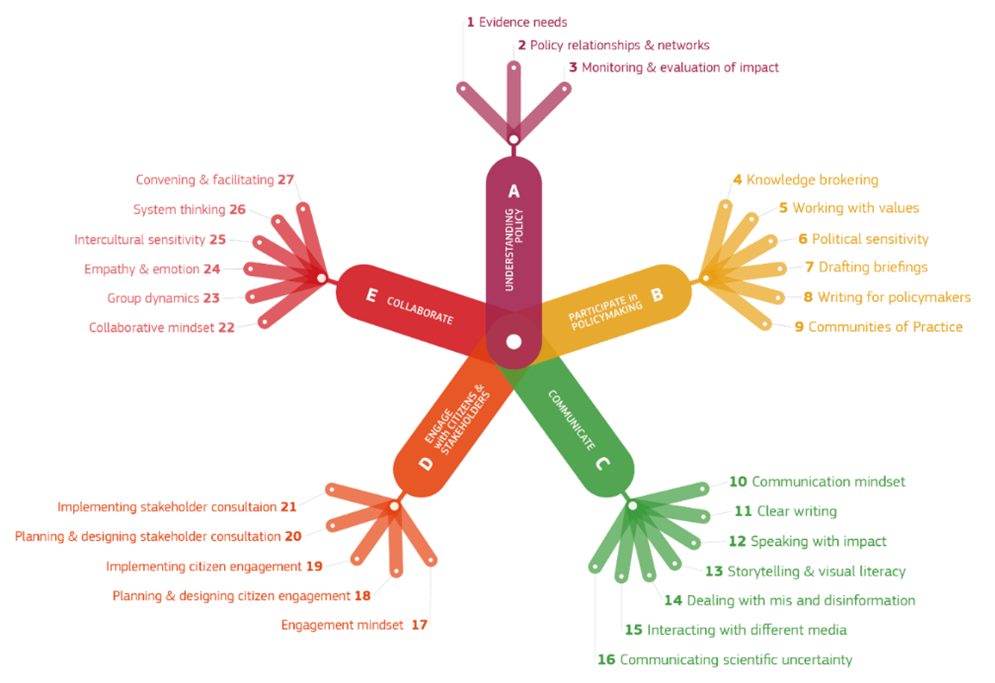

The secondframework, 'Science for Policy', has been designed for researchers advising policymakers and organisations working at the science-policy interface. It comprises 27 competences across five clusters: understand policy, participate in policymaking, communicate, engage with citizens and stakeholders, and collaborate. The framework assumes organisations already possess primary research skills and focuses on the supplemental competences needed to navigate policy.

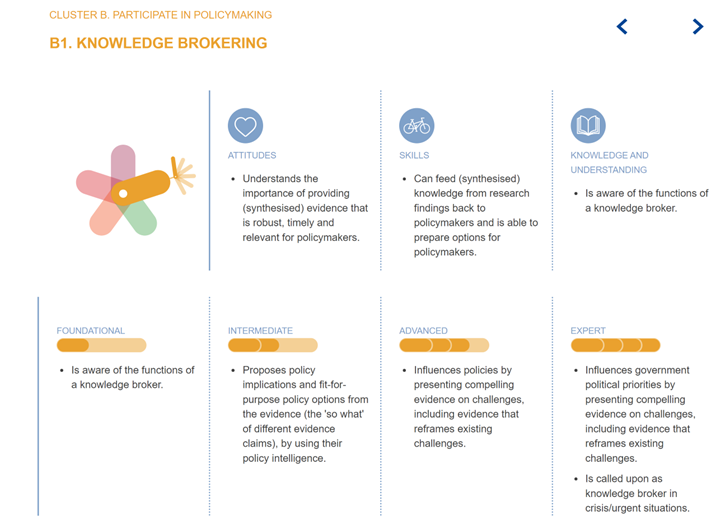

The frameworks include four proficiency levels for each competence:

- Foundational: You are operational, but need guidance and support in this competence.

- Intermediate: You are independent for normal tasks that require this competence.

- Advanced: You can solve hard problems that require this competence and coach colleagues.

- Expert: You have deep experience and are a point of reference for this competence.

A closer look at ‘Science for Policy’

The 'Science for Policy' competence framework outlines a collection of competences needed to work at the interface between science and policy, or as a scientific adviser to policymakers. The competences are grouped into 5 clusters. For each competence it presents skills, attitudes, knowledge and understanding, as well as typical activities separated by level of competence.

While many of the competences overlap with the framework for policymakers – notably the clusters ‘communicate’, ‘engage with citizens and stakeholders’, and ‘collaborate’ – are very similar, the competences portrayed here are different than the ones you need to be a successful “pure” scientist. The assumption behind the framework is that any researcher, who would be in a role to advise policymakers from a scientific perspective, would already master the competences needed in their scientific field. But even the most experienced researcher might struggle with a new advice function. A policymaking audience is not a scientific audience: policymakers listen, read, and understand differently, therefore scientists need to adapt, if they want to be successful advisers.

As a scientist who is advising policymakers, you need to understand their question, and be able to give a short – at least relative to a scientific publication – but not oversimplified answer. Notably, sometimes even the policymakers you will be working with as a scientific adviser might not clearly know which questions they actually need to know about, and which can be answered by science.

The competence framework empowers researchers and organizations to ensure that the most useful and robust evidence is understood and presented timely for policymaking. It includes research synthesis skills for distilling the best available evidence, community management to leverage the wisdom of crowds, systems-thinking and cross-disciplinary integration, and strong communication and citizen engagement skills. The framework also requires political intelligence and listening skills to discern when to present key facts and interpret the science in its political context.

Importantly, no one person is expected to master all the competences in the framework. But an organisation covering the full portfolio of scientific advice for policymaking, like the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, should have staff that can cover all the competences collectively as a team.

Applying the competence frameworks

Together the competence frameworks aim to bridge the gap between science and policy, fostering a mutually beneficial ecosystem that reinforces trust. Democracies are faced not only with policymaking challenges, but also with disinformation and distrust, further increasing the need for innovative, evidence-informed policymaking that is trustworthy and transparent. Policymaking needs science.

The competence frameworks help addressing these challenges in multiple ways: both models provide a valuable reference point for professional development and career progression, curricula design, and policy development.

The European Commission developed the two competence frameworks and employs them to design training courses and assess the curriculum, but they are – by design – applicable beyond this context. Both frameworks are publicly accessible for application and experimentation. Like the professions they represent, these frameworks are designed to adapt over time and can be tailored to reflect the specific challenges of another context. Advancements in policymaking and science for policy necessitate that organizations implement systematic and creative strategies for capacity building, incorporating more hands-on learning experiences. Similarly, individuals and teams involved in policymaking and research need to evaluate their aggregate competences and dedicate resources to enhance their skills, knowledge, and attitudes. To facilitate this, the European Commission has created a self-reflection tool, Smart4Policy, which allows policymakers and researchers to reflect on their different competences and receive tips and resources to improve for each competence.

Photo by Denisse Leon on Unsplash

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.