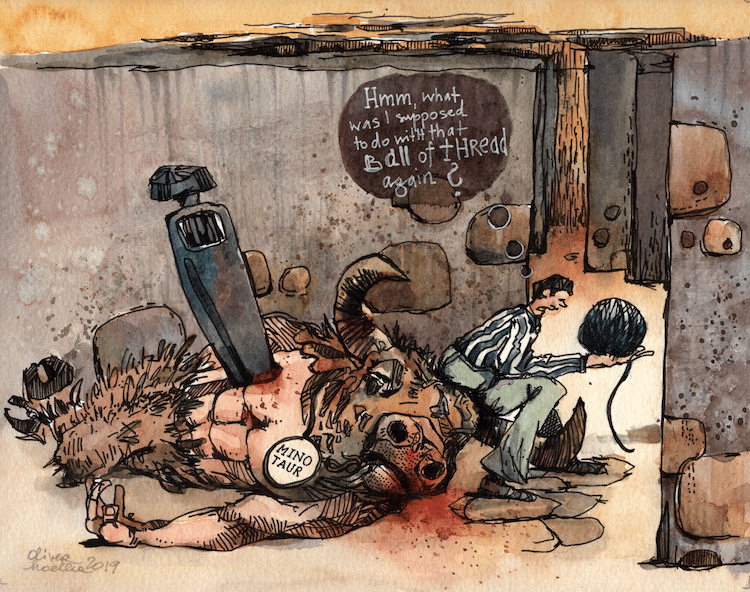

Picking up a project sometimes means getting stuck in a labyrinth.

A labyrinth. The labyrinth. Dust on the floor. Rough stone walls. Guttering torches overhead flickering shades of yellow and orange. Long shadows. Little light.

Theseus, the hero, pads onwards. A naked blade gripped tightly in one hand, a ball of string cautiously unwinding through the sweating fingers of the second. Somewhere ahead, at the centre, the minotaur awaits.

Scientists are often prone to mythologising their endeavours, and the legend of Theseus offers a more fertile metaphor than most. The lonely protagonist warily stalking his or her prey through the darkness of an elaborate maze. Gradually narrowing down the places where the truth could be hiding, each publication an incremental step forward until some revelation, some climax, is reached. The secret at the labyrinth’s centre is cornered and vanquished.

A key difference of course is that Theseus had his ball of string. Even if he got lost, he could retrace his footsteps right back to the start. That tends not to be how it is these days, at least for the scientists in the labyrinth.

These days, it’s more like a relay. The sword – but not the string – passed from hand to hand as each new researcher takes up the challenge of the maze.

These days, it’s more like a computer game, with multiple and possibly unlimited continues. Each time the swordholder departs, a new recruit steps in to take their place. But each of those changeovers entails a loss of accumulated experience, and occurs at a greater distance from the start. And as in computer games, things acquired in the previous iteration are lost or incompletely retained.

No ball of string. Just press on into the labyrinth.

Mobility is almost universally encouraged in scientific careers, offering a chance for international experience, a broadening of expertise and exposure to different research philosophies. But gone are the days when a paper could consist of a single technique applied to a simple problem. A typical research project will now span multiple people who haven’t overlapped in time; it’s a train that trundles, then hurtles, and sometimes meanders, with people getting on and off at each waypoint on the journey.

All too often, those people are not given the thread. Picking up a project can mean not knowing how it started, what routes have already been attempted, or where the current line of reasoning leads back to. It means just pressing on into the dark.

It’s this change, this depersonalisation of the heroic narrative, that makes it more important than ever for the group leader to communicate the project’s whole arc. Only the group leader will have a perspective on the whole sweep of that line of enquiry, and even they are unlikely to routinely think about it over that kind of conceptual distance.

The background and the big question that were the departure point for a story must not be lost. Benchwork inevitably demands a focus on minutiae, on fine detail, but it’s both empowering and essential to know how that story fits into a bigger tale.

For young scientists, not seeing how their project relates to a big question and not having the familiarity of thinking about things along a grand narrative sweep are two of the major stumbling blocks that come on the way to transitioning to scientific independence. It’s hard to tackle big questions as an independent scientist if you’re not used to seeing them, if they’re lost somewhere in the murk behind you, with no means of retracing the way.

A thread feels like a small sliver of a thing, but it stretches a long way.

Originally posted on Total Internal Reflection - here.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.