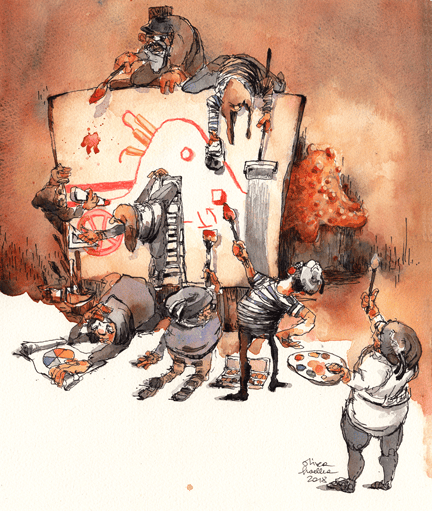

A scientific field’s progression to maturity mirrors the production of an oil painting.

One of the real joys of preparing a lecture is the opportunity it gives to step back and view a field all the way from its inception up to the present day. That more removed perspective grants the equivalent of a fast-forward reel, a breakneck race along the whole arc of discovery from the now-distant past up to the ongoing present.

The narrative itself, from this perspective, is surprisingly standard – but no less gripping for its familiarity. The intriguing and puzzling early observations, often from disparate geographical locations, eventually coalescing to form a foundation of basic knowledge, then the refinement of techniques to probe the new phenomena, next the gradual delineation of main areas and questions, then the radiation into specialised subcommunities to tease out increasingly detailed analysis of individual components and their interactions, and at last the final synthesis of all components to encompass the whole body of work in a system-level whole whose edges – like fractals – remain blurry no matter how much effort is expended. Like “Ben Hur”, it’s a story with a cast of thousands, but one that swells as the narrative progresses. The stories start with a few pioneers in the desert and end with the crowds in the Coliseum.

It’s a process too that strongly resembles the production of an oil painting, with the successive glazes (layers) being built up on top of each other to gradually complete the artwork. First the underpainting on the canvas, then the sketch of the main areas, then the addition of blocks of colour, then at last the fine details. Each layer depends on what’s gone before, and the overall artwork emerges and comes into focus over time.

In the studio of a successful artist (Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyckbeing outstanding examples), the completion of canvases was very much a group effort. Members of the studio would fill in areas, with different assistants and copyists specialise in different aspects – clothing, hands, animals, furniture, and so on. In science, people’s technical specialities play a role in what aspect they address (inevitably, they may squabble over who does something best, and disagree over whether others’ work is good enough to merit inclusion on the canvas).

At some point, each scientific effort, each canvas, reaches a kind of end, with the field’s founders at or approaching retirement, and most areas worked up to a finish of sorts. It may not be complete – in fact, it will never really be complete – but it may be sufficiently finished for exhibition. A chance for others to admire the community’s work, their diligence, their skill. Might it receive an award? Some fields (like Picasso, Michaelangelo, Leonardo) receive recognition within their lifetime and a lucky few the ultimate accolade of a Nobel prize; others (like Vermeer, Van Gogh) languish undiscovered or unheralded until after their founders have died, if at all.

Upon the completion of one of these scientific canvases, the fate of its creators is varied. Some continue to hang around and improve the details ever more, others move on and start work on a new canvas; a few may decide something is not right, and start painting over the old material. Eventually, a new tool or technique will be invented that allows a reassessment of the work done before, and a refinement to a level of detail previously unimaginable (remember your first experience of HD TV?).

These canvases pose a challenge for the young scientist. What is the best contribution to make? Or rather, when is the best time to join in? Is it preferable to start off with the underpainting and hope that you’ll still be around to see the canvas come to fruition? Or to join the crowds working on the fine details of a field which is already nearing some level of completion? It’s best, probably, to try to arrive just after the main blocks of colour have been added, giving you the opportunity to supply the details.

Whichever way you go, you do need to be able to see the whole painting, even if you only work on one detail of it. Step back and enjoy the whole thing. It’s the work of many hands, and many years, with many false starts and readjustments, many infinitesimal tweaks, but a masterpiece nonetheless and a monument to human endeavour.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.