FEBS Excellence Awardee spotlight: Kim Kampen

Kim Kampen is an assistant professor and group leader at the Department of Radiotherapy at Maastricht University, the Netherlands. After a PhD at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands) on vascular endothelial growth factors in leukemia, and a postdoc at KU Leuven (Belgium) on ribosomal gene defects in cancer, she now leads a research group studying metabolic reprogramming in cancer. Kim was selected for a FEBS Excellence Award in 2021.

What is your current research focus?

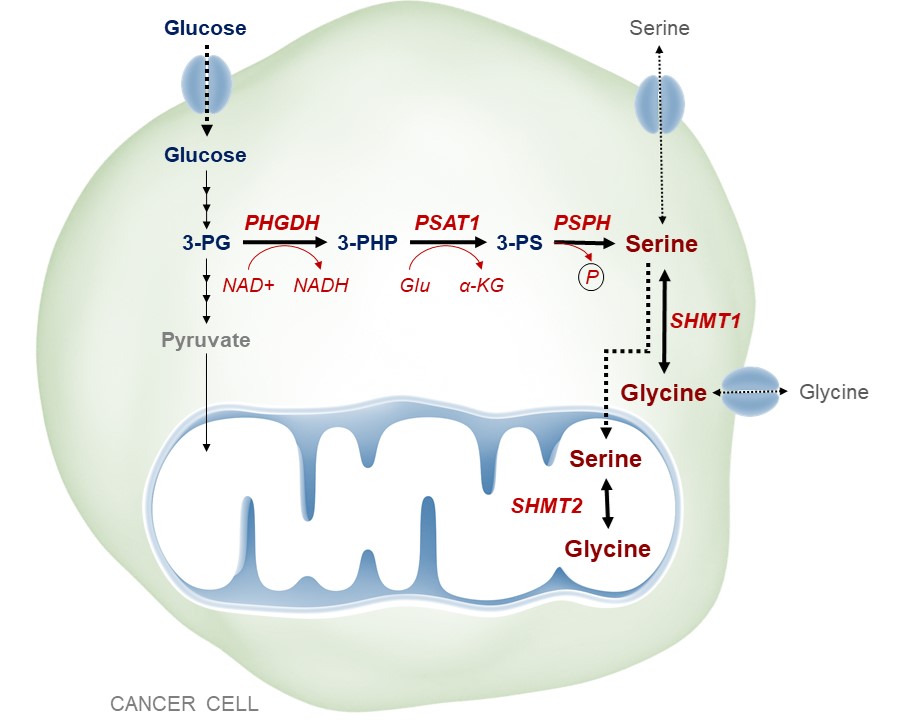

My research is centralized around metabolic rewiring in cancer with a special focus on serine and glycine metabolism hyperactivation. The research can be subdivided into three major topics: identification of new drivers of serine/glycine metabolism in cancer; overcoming therapeutic resistance by targeting serine/glycine metabolism in cancer using our re-purposed serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) inhibitor sertraline; and defining the role of tumor-derived serine/glycine pathway metabolites as biomarkers for cancer progression and therapeutic responses.

Lab webpage: https://www.maastrolab.com/kim-kampen-lab

What’s exciting in this field at the moment?

Metabolic rewiring in cancer cells has been a hot topic for years already. Cancer cells can rewire in such a way that they are more resistant to current therapeutic approaches. In this context, we aim to target the metabolic requirements of the cancer cells, leaving the normal cells unharmed. A most exciting aspect is the interaction between tumor cells and their microenvironment, especially how cancer cells can modulate the tumor microenvironment by providing nutrients. This is a research line we aim to explore further in our lab and in clinical trials.

What drew you to work in this area?

I was always intrigued by cancer research during my studies as well as during my PhD and postdoctoral work. Understanding the way cancer cells adapt by modulating their metabolism is a unique and big puzzle, with therapeutic implications. The ultimate goal is to provide more-specific therapeutic opportunities for cancer patients, to give them a better life expectancy and a better quality of life due to lowering therapeutic toxicity.

What would be your advice to PhD students and postdocs who would like to eventually start their own lab?

Start your plans early, think things through and make them happen. Do not be daunted by having to keep trying; you will learn a lot from it along the way. I always give the example of the first Harry Potter book to students. It was rejected 12 times before a publisher took it, and is now part of the best-selling series in history. So sooner or later a strong research proposal should succeed and you will stand out from the crowd.

Apply for fellowships and small grants early on, as well as travel grants, etc. They are easy to obtain and good for your career building. Join a big renowned lab for a while, which is outside your comfort zone. You’ll work hard and get a lot out of it: it will allow you to develop novel ideas, think out-of-the-box, learn a lot of new things and new possible applications to your own research. Then for your postdoc, find a promising new rising small lab in a huge institute. Help to build the lab with your expertise; it will make you fully independent, allow you to develop your own ideas and produce some important papers. This provides solid ground to start your own lab.

How have you found being a group leader?

With all the hurdles and new tasks, quite hard. It is very difficult to start up a lab, get funded and find the right team to move things forward. You might think you can do whatever you want being a PI, but it’s not the case: suddenly you need to get your teaching qualifications and carry out teaching duties, as well as manage people, and have responsibility over all sorts of things – financially and technically for lab equipment, for example. So your task list will be growing and you have less time to spend in the lab, while that’s the thing you love most, at least in my case. I try to keep on doing experiments whenever possible and train my team in the best way, so they are fully equipped and experienced.

What do you see as the most important role of a group leader?

Teaching, training and people management to create the most strong, motivated, happy and supportive team possible, in which everyone can be themselves fully, has opportunities to develop themselves in the best way and feels valued for all their research efforts. I try to give help and support in any way possible (teambuilding, material wise, expertise, mentally) while giving team members lots of freedom and responsibility for their project.

How will the FEBS Excellence Award help you as an early-career group leader?

It provides me the opportunity to have a budget for equipment and experiments to build new ideas and set up new research lines. It provides the best opportunity to get a lab started for sure. In order to get grants you need preliminary results. This grant allows me to do this, which enables me to start and get new funding resources.

What would be one wish to improve the bioscience research landscape?

Provide more basic research funding in academia. The current system hardly allows you to do off-record experiments. While these experiments are often expensive, they may give us new ideas and provide valuable out-of-the-box data, to frame science, build new concepts, and move science to the next level. There is no place for failure in science – career-wise one is on a continuous train that cannot be stopped – and there is hardly any time for side projects because of all the extra duties such as teaching and pressure to write grants in order to just sustain the lab.

Top image of post: 'Cells from cervical cancer', from the National Cancer Institute on Unsplash.

Join the FEBS Network today

Joining the FEBS Network’s molecular life sciences community enables you to access special content on the site, present your profile, 'follow' contributors, 'comment' on and 'like' content, post your own content, and set up a tailored email digest for updates.